The Healer

Life is full of uncertainties for the residents of West Baltimore. A lot of them count on Doctor Z, and he’s good for it every time.

by Mark Puente ’05

The doctor picks up three syringes and walks toward a smiling 9-month-old boy in a Batman onesie. He tightens a tourniquet around Dylenn Jackson’s arm as his mom coos at her curly-haired son.

The first needle pierces Dylenn’s skin, and there comes the predictable reaction.

“Oh, momma’s big boy. You’ll be OK,” said Dr. Michael Zollicoffer. “Mean Dr. Z still isn’t done yet.”

It is 9:30 on a Wednesday morning at Life Care Plus, an urgent-care clinic near Sinai Hospital in Baltimore. As usual, Dr. Z doesn’t know when he’ll finish seeing patients that day. They come at all hours, and he’s committed to anyone who comes through the door.

Zollicoffer ran his first marathon at 15. But since 1985, when he graduated from UNC’s School of Medicine, the former high school track champion has been on a sprint that doesn’t have a finish line.

His patients are African-Americans in West Baltimore — the part of the city that drew worldwide attention in 2015 following the death of Freddie Gray while in police custody. Many of them can’t afford basic essentials, let alone quality health care. At 57, Zollicoffer sometimes feels as if he’s on a one-man crusade to eradicate what he calls the “anvil of poverty.”

He built his neighborhood clinic with about a half million dollars of his own money. You will not find multiple nurses and doctors bouncing between examination rooms. He’s the only doctor in the place, sometimes treating 30 or more patients a day. His exam rooms don’t have computers; he writes notes in paper files. Besides slowing him down, he says, computers hamper face-to-face interaction.

He jokingly calls it his “Taj Mahal” — a clinic “where rich people and poor folk come.” He admits that at times he has to “rob Peter to pay Paul” to keep it open.

Most days he starts early and stays well past darkness. A locker room, kitchen and bed in the rear of the clinic enable him to stay overnight when needed a few times each month. If patients can pay Dr. Z, they do. If not, they don’t. He refuses to create barriers to health care.

“I can’t watch anybody suffer, rich or poor. In here, I fix it.”

An enormous fish tank greets Rosa White, left, and her granddaughter, Lakiyah Gales, when they visit Zollicoffer at the clinic he built in Baltimore. (Photo by Steve Ruark/AP Images for the Review)

Becoming a Tar Heel

Anybody who doubts that Michael Zollicoffer approaches all this with good humor has not seen him in front of a captive audience.

For years, he has returned to Chapel Hill to help with the work of the General Alumni Association, and on Saturday, June 11, it is his turn to tell his Carolina story to the GAA’s Board of Directors. As his time late on the agenda nears, something strange happens. Committee reports get shorter, and a couple of people explain that they’re banking time so Dr. Z will have more of it.

You might find him dressed to the nines for a golf tournament — all knickers and argyle — but on this morning his white shirttail is out fore and aft under a dark suit jacket, his demeanor equally relaxed. He’s not sure where to start: “I been here since I was running around as a 2-week-old in diapers. When you grow up as a little kid and see a man walking down the hall pulling his hair out and you just wondering — this man is losing his mind over some game.”

He’s firing like a Thompson submachine gun, and it’s kicking up bursts of laughter around the room already. The “man” is his father, Lawrence Zollicoffer ’62 (MD), one of the first black people to be admitted to UNC’s medical school. Michael would do his undergraduate at Maryland-Baltimore County, so by the time he got back to Chapel Hill, he was playing catchup on the dream he inherited before the elder Zollicoffer died young.

“I was on the waitlist for medical school, and probably two days before class I got the call. So away I dashed. I said, ‘Baby, I been waiting for this.’

“Back then I was not the person you see now. I was so shy, very introverted.” A shriek comes from someone in the gallery who knows better.

“They said go to the Happy Store and get the keg. I didn’t know what a keg is — I never drank beer in my life. Keg — I thought that was a wooden barrel, I thought they wanted it for ambience, you know, split it in half. I said, where do you get this keg? They said at the Happy Store. The Happy Store? What the hell?”

One phrase he spat out over and over for 20 minutes: “I was becoming a Tar Heel.”

Elected president of his second-year class; founded the UNC chapter of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity (“I could never say no”); cheered Dean Smith’s first title; won the Chicken Bridge road race in Chatham County two years running; got Al Jarreau’s autograph. And, just after he was elected third-year president, came up short academically and had to do the second over again.

Now he has them in stitches. Then, he hushes the room with his father’s story.

The 10-year wait

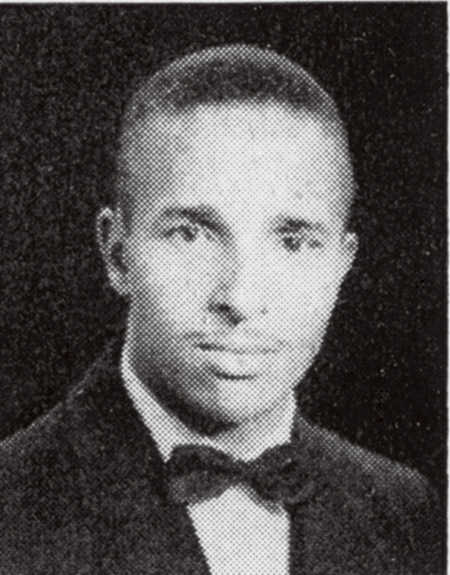

Dr. Lawrence Zollicoffer, father of Dr. Michael Zollicoffer (1960 Yackety Yack)

He earned the title Dr. Z as a child making house calls with his father. The elder Zollicoffer, a child genius, enrolled at age 13 at N.C. A&T State University and graduated at 17.

And he had multiple medical school offers but not the one he wanted. His son told the GAA directors the story.

“The world was at his feet, he could do anything. He grew up just like everybody else — a little kid wishing to be a Tar Heel. He didn’t look at any problem, racial barriers or not. He just knew that that’s what [he] wanted.

“Child prodigy. He could go to any medical school he wanted, and he refused to go.” The storyteller paused. “ ‘I’m gonna be a Tar Heel.’

“So he waited, and he knocked. Nobody let him in. He waited. He knocked. Nobody let him in. On and on for 10 years he waited — not to be a doctor — to be a Tar Heel. Because he just wanted to be like everybody else. But the time wasn’t on his side at that time. Dad sat there for 10 years, and the letter never came.”

He’d worked farm fields as a child; now he bided his time teaching agriculture in the schools in Belhaven near the coast.

Meanwhile, Zollicoffer said, the top administrators in the medical school had been strategizing how to get African-Americans into the school. Finally, the ice broke for Lawrence Zollicoffer. He was the fourth black to be admitted. “Not a chip on his shoulder,” his son said.

While he was in medical school, his family was rubbing shoulders with greatness on Caldwell Street. Educators R.D. and Euzelle Smith lived across the street; community activist Frances Hargraves a couple doors down; also on the block, future state Supreme Court Chief Justice Henry Frye ’59 (JD), civil rights lawyer Julius Chambers ’62 (LLBJD) and student counseling Dean Hayden Bentley Renwick ’66 (MEd).

Zollicoffer moved his family to Baltimore, where he’d done his pediatric residency at Sinai Hospital. He opened Garwyn Medical Center, one of the city’s first minority multicare medical facilities. As he built the practice, he frequently made house calls for patients who were too sick to visit the clinic or who didn’t have transportation.

Cancer took him from his dream when he was 45. A lecture series at Carolina is named for him.

Madison Mayo, 7, peers out of an examination room as the doctor takes a call across the hall. (Photo by Steve Ruark/AP Images for the Review)

Healer, mentor

The clinic in West Baltimore is a place where most patients know each other from the neighborhood. Zollicoffer treats the children and grandchildren of his earliest patients. He estimates he has cared for more than 30,000 of them in the past 30 years.

Dr. Z shares a moment with 4-day-old Meadow Ross. Zollicoffer is the only doctor in the place. Trained as a pediatrician, he follows many of his patients through life. “They don’t want to leave.” (Photo by Steve Ruark/AP Images for the Review)

The number is high in part because, though he’s trained as a pediatrician, he can’t let go of his patients as they age. “My pediatrics is now geriatrics because I just don’t do things that make sense.”

He says he took an oath “to be a physician, not a specialist.” He believes primary-care doctors lose basic clinical skills when they don’t treat patients with basic ailments. He used the example of a primary care physician sending a patient with a rash to see a dermatologist.

He also believes technology has depersonalized medicine. “Doctors should put their butts back into a chair and teach. Patients aren’t a computer chip.”

He hasn’t worn a white lab coat in decades. He boasts he can draw blood from a patient in less than 30 seconds — he doesn’t want to send patients to another clinic for a simple procedure.

Furthermore, “doctor,” he insists, doesn’t fully describe what he’s doing. “I’m a healer,” he says from atop a stool in an exam room. “Doctors don’t heal, healers heal.”

Between juggling patients and running the clinic, Zollicoffer mentors young people. His goal is to steer them into the medical field to be doctors, nurses or paramedics. He allows young people training to be paramedics to intern in the clinic. His mentoring often extends to his staff.

His 19-year-old receptionist, Kaylin Sneed, is studying to become a nurse. She said she didn’t understand the questions Zollicoffer was constantly asking about her life. She felt annoyed until she realized he was trying to help her make better choices.

“Whatever I need, Dr. Z can help me,” Sneed said. “He doesn’t just focus on medicine. A lot of people say, ‘Dr. Z is the only doctor who will do this for me.’ ”

He tries to instill in his proteges the importance of earning a degree that can better their lives and those of family members — guidance they might not get elsewhere. He makes sure they know he wasn’t a great student himself, didn’t leave with honors or extra tassels hanging from his cap.

At times, Zollicoffer has a hard time convincing parents to get on board. Most, he says, don’t understand what it means to get a child into medical school. But the parents know what it means for their children to get a job. Students he has mentored have landed at Carolina and other schools.

“I have a pipeline of students. I want that kid that everybody thinks can’t do it.”

Shaitia Martin was a 10th-grader interested in medicine when she met Zollicoffer; she now studies public health at the University of Miami. This summer, Martin was in Chapel Hill, at Dr. Z’s urging, for eight weeks taking courses with the N.C. Health Careers Access Program. (Photo by Steve Ruark/AP Images for the Review)

Shaitia Martin met him when she was in 10th grade. She had told a family friend she wanted to be a doctor, and the friend put them in touch. Martin said she was supposed to shadow him in the clinic for only two weeks. “It turned into two years.”

Now a junior studying public health at the University of Miami, Martin said Zollicoffer has always suggested high school and college courses that will put her on a path to be a doctor. They still talk on the phone once a week.

This summer, Martin was in Chapel Hill, at Dr. Z’s urging, for eight weeks taking courses with the N.C. Health Careers Access Program. She hopes to be a pediatrician and build her own pipeline of students to push into the medical field.

“His interactions with patients are unique. I’ve never seen a doctor get to know each patient on a personal level. He grows with them. It’s their journey and his.”

“This ain’t work; this is life,” says Zollicoffer, shown with patient Meshawn Allen. “What I do is not normal. Life consumes me; this is a part of that life.” (Photo by Steve Ruark/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

Zollicoffer shares a laugh with patient Dayne Guest. (Photo by Steve Ruark/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

Zollicoffer checks the ears of young patient Marley Mayo, held by her mother, Ashley Mayo. (Photo by Steve Ruark/AP Images for Carolina Alumni Review)

When Patrick Sweet graduated in 2013 with a biology degree from Morgan State, he wanted to be a researcher. Then a friend introduced him to Zollicoffer. Sweet started medical school at UNC in August; he plans to be a primary-care physician.

He said the doctor’s best advice was to get a job and not fret over the application process for medical school. “Before I met him, I was lost,” Sweet said. “He guided me into medical school.”

Sweet, too, shadowed in the clinic, where he observed the ways medical care intertwines with social, racial and economic problems in Baltimore.

“Dr. Z looks like me. You don’t see a lot of African-American doctors giving back to the community in Baltimore. He is unique.”

Father of one, now unmarried, Zollicoffer isn’t religious, but there’s a preacher-like quality to his counseling. He sounds like one when his staccato advice and his laughter bounce off the walls of exam rooms.

One patient, he said, complained about “a noose around her neck.” During exams, the woman always talked about how miserable her marriage made her. Zollicoffer realized the marriage contributed to her health issues and suggested she divorce her husband. Did that cross a line? No way, he said. She knew a divorce was the answer, but she needed to hear it from somebody like him. She took his advice, and months later her health was improved.

The anger underneath

Dr. Z was told he missed passing his second year of medical school by half a point. Med school had to share time with his quest to become a Tar Heel — it was that year that he got the fraternity chapter started, something of which he’s very proud. Phi Beta Sigma is alive still at Carolina, with some 300 graduates now; fraternities, Zollicoffer said, are a positive force in the black male college-retention rate.

He says he would do it again because of the lessons it taught him. He now preaches that to anyone who will listen.

“Thousands can relate to that story,” Zollicoffer said of repeating the year. “How many times do you hear a story where someone doesn’t have a failure?”

He would become the first second-generation African-American to graduate from UNC’s medical school.

Thurman W. Zollicoffer Jr., a lawyer and former Baltimore city solicitor, said the man whose shoes his cousin fills is still a legendary figure in the city 40 years after his death. That, he said, is one reason Dr. Z works so hard to help people.

“A lot of it is his deep and abiding love for his father,” he said. “He feels like he has to go every second; his engine burns very hot. He doesn’t know when it will end.”

Baltimore is home to Johns Hopkins University, one of the world’s top hospitals, but its medical centers are worlds away from Zollicoffer’s inner-city patients.

Dr. Z takes a phone call in his West Baltimore clinic. He lives nearby and sometimes sleeps in his clinic so he’s quickly accessible to his patients. (Photo by Steve Ruark/AP Images for the Review)

He could afford to live in the suburbs, far from rampant murder, streets full of abandoned homes and panhandlers on corners. Instead, he lives in the impoverished neighborhood alongside his patients. His house is not far from where black smoke poured into the sky after looters stripped a CVS pharmacy bare during the 2015 riots.

It’s minutes from his clinic. That allows the doctor to return quickly when a patient calls late at night. It’s rare that the calls roll to an answering service.

“What I do is not normal. Life consumes me; this is a part of that life. I’m not burned up. This ain’t work; this is life.”

Underneath the sunny side his patients see, there also is anger. He’s deeply disturbed by the poverty in his backyard, perpetual over generations. Zollicoffer has no patience for political correctness.

Corporate profits, he said, have taken precedence over patient care. Doctors are too willing to do procedures that cost hundreds or thousands of dollars because insurance companies will pay the bill.

He rails that the pharmaceutical industry and corporations make billions in profits by hawking drugs to black communities for high cholesterol and other ailments that he calls “Dr. Oz syndromes.”

In talks to community boards and nonprofits, Zollicoffer tells people that boys don’t need to be circumcised and mothers don’t need to come see him when their babies have gas.

As politicians at the federal and state level debate health-care policies during this election cycle, Zollicoffer called President Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act nothing more than “insurance reform that has given everyone access to a bad apple.”

The act gave everybody access to health care but didn’t go far enough to reform the method of delivery, he said. He believes that the country’s health-care system should be dismantled and rebuilt from scratch, starting with the way patients are diagnosed. His biggest critique is that money and profits play too large a role in health care and that the act didn’t minimize the role of big pharmaceuticals and corporate medicine. He points to other countries, including Canada, where care is less complicated.

Sometimes seeing 30 patients a day, collecting only from those who can pay, somewhat weary of the Affordable Care Act and maintaining living quarters at the clinic for the nights he needs to stay, Zollicoffer is nonetheless energized by the work he carries as his father’s legacy. (Photo by Steve Ruark/AP Images for the Review)

They know he cares

After Zollicoffer finished with Dylenn Jackson’s vaccinations, Dylenn’s mother sat on the table for her exam. Afterward, he declared her healthy and told her he’d see her in a few months for Dylenn’s next visit. She asked about her son’s hernia. The doctor reassured her it was not a problem.

“I can always call Dr. Z,” Deairra Evans said. “I can tell him anything. If Dr. Z tells me something, I do it. I trust him.”

Next was 15-year-old Kayla Caldwell, who’s been coming to Zollicoffer since she was born. Kayla turned her head and smiled when the door opened.

“What do you say, baby?”

“Hi, Dr. Z.”

He quizzed Kayla about any current medical issues. He asked whether her parents were married, how many people lived in her house. He asked her about the most prevalent sexually transmitted diseases. She remembered the answers from the last visit.

“Are you smoking a lot of weed or a little?”

“None, Dr. Z,” the teen replied, laughing.

“What about drinking? You drinking a lot?”

“I don’t do anything but play sports.”

He then wanted to know the 10th- grader’s plans. Kayla wants to be a dietitian and go to Southern Cal or UCLA.

He told her she didn’t need a college degree for that field. He encouraged her to explore all options. Zollicoffer cares for Kayla’s parents, siblings and most people in her neighborhood. Her friends, she said, always talk about his questions.

“We think it’s funny,” Kayla said. “It shows us he cares.”

He paused as he walked out the door: “Straight talk in the ’hood is the only talk that people know.”

In the adjoining exam room sat an 18-year-old woman in jeans. A yellow shower cap covered pink curlers in her hair.

“Hey baby. What’s going on today?” Zollicoffer asked Sarina Harrison.

“I got my prom and momma’s birthday this week,” she replied.

“Priorities; I got you. I want to get you right for your fun things,” Zollicoffer joked before asking about her mother and sisters. He is the only doctor she has ever visited. She said a specialist could have treated her current ailment, but she trusts only him.

“Dr. Z has been there for me,” Harrison said. “I can call him on his cellphone. He’s honest and straight to the point. I love it. He makes people feel good.”

Zollicoffer said he plans to grow old with his patients.

“They don’t want to leave,” he said. “This has become more than an urgent care. This is a life-care center. If you walk through that door penniless, I am not asking you for anything.”

He then twisted the door handle to an exam room where another patient waited. Within seconds, his and the woman’s laughter echoed throughout the hallway.

Mark Puente ’05 is a journalist who recently rejoined the staff of the Tampa Bay Times after two years as an investigative reporter with The Baltimore Sun.

There’s nothing casual about Dr. Z when he returns every year for the Black Alumni Reunion golf tournament. (Photo by Jerry McKellar ’16)

Giving Back, Raising Hope

Michael Zollicoffer’s accomplishments have been recognized at Carolina.

He’s earned the medical school’s MacNider Award as well as honors for achieving excellence in immunizing children and providing excellent Medicaid-compliant services. He has chaired the medical school’s board of visitors and also serves on the GAA’s Board of Directors; its Black Alumni Reunion honored him with the Harvey E. Beech Outstanding Alumni Award in 2010.

UNC’s chapter of the Student National Medical Association established the annual Zollicoffer Lecture, now the Zollicoffer-Merrimon Lecture, in 1981 to honor Lawrence Zollicoffer ’62 (MD). The program works to increase the awareness of minority-health issues and introduce students to minority role models.

The Zollicoffer family also established the Zollicoffer -Allan Cross Community Health Fellowship to encourage medical students, especially underrepresented minority students, to experience community medicine and to learn about the health issues related to minority and medically under-served communities.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.