When the Berlin Wall Came Down

Michael Martine ’91 took this photo of protesters breaching the Berlin Wall in 1989 when the international studies major was there on study abroad.

Alumni, Faculty Recall Momentous Change in Berlin

Michael Martine ’91 had a front-row seat for history in the making.

When the Berlin Wall began to fall on Nov. 9, 1989, he was sitting on top of part of it, his feet dangling as he looked into the eyes of gun-toting East German soldiers, who until that day had been charged with preventing such breaches.

The night could have easily dissolved into violence but it didn’t, and for many the occasion has come to symbolize a peaceful end of the Cold War.

“It could have gone horribly wrong but it ended up going amazingly right,” said Martine, an international studies major studying in Germany at the time.

Martine was one of more than 175 people who attended a GAA-sponsored panel on Nov. 9, the 25th anniversary of the wall’s fall. UNC faculty members Konrad Jarausch, Klaus Larres, Priscilla Layne-Kopf and Graeme Robertson spoke not only about that moment in history, but its continuing repercussions in Germany and beyond.

Once the wall was down, reunification of the formerly communist East Germany with democratic West Germany wasn’t easy.

“Switching from collectivism to individualism is a tough task,” said Jarausch, a professor of European civilization.

The Berlin Wall was built in 1961 to prevent people fleeing the communist East Germany, which fell under the domain of the Soviet Union following World War II, as West Germany aligned with the western Allies.

Michael Martine ’91 took this photo of East German guards patroling on top of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Event moderator Lloyd Kramer, professor of history, noted that during the wall’s 28 years of existence, 148 people were killed trying to cross it.

After the wall’s fall there were struggles culturally, financially and politically.

Former East Germans were in the minority in the newly reunified Germany and sometimes struggled to get their opinions heard, Jarausch said.

Martine saw firsthand how rapid the changes were after reunification, even in the landscape. He remembers whole city streets changing overnight as shops and cafes converted to import-export businesses where people from places like Poland could come and buy goods they couldn’t get at home.

Layne-Kopf, an assistant professor of German, shared poems and other artwork from East Germans from that time that expressed feelings of cultural loss and ambivalence about reunification.

Larres, a professor in the curriculum in peace, war and defense, talked about the concerns of other European countries over Germany’s reunification. Twenty-five years ago countries like Great Britain and France looked to Germany’s fascist past and worried about what a reunified Germany would do with its newly reintegrated power.

He also noted how these worries partly promoted European integration efforts, such as the eventual creation of the euro, the official currency of the eurozone.

Robertson, an associate professor of political science, talked about the impact of the fall of communism across Europe and noted the differing success rates of formerly communist countries. Some, like Hungary, have done well adjusting to democracy while others, like Russia, have become autocratic. He also noted Russia’s income inequality. “It basically went overnight from being Finland to being Brazil,” he said.

One thing all the panelists could agree on was a certain level of amazement and thankfulness that the wall’s fall happened so peacefully.

“This is quite extraordinary for German historians — we have a happy event to talk about,” Jarausch said. “On the whole this is still a development that blows my mind.”

Martine expressed a similar amazement, especially in hindsight. One wrong move and the wall’s fall could have turned into another Tiananmen Square, the violent putdown of protests in China just a few months earlier, but it didn’t, he said.

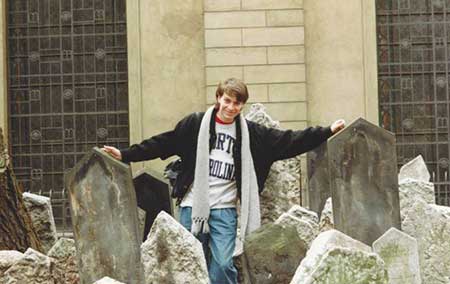

Martine ’91 was a study abroad student in Berlin when the wall

came down.

“This was such a deciding moment in political history where things went right,” Martine said.

Martine, who works as IBM’s director of supply chain transformation, brought his 10-year-old son, Cal, to the event and said such continuing-education events were one of the reasons he liked staying engaged with the University.

He said he sent boxes of wall pieces home when he was studying in Germany, but kept none for himself, as the memento most important for him was that he got to be part of such an important piece of history.

Also at the event was Kate Enchelmayer ’74, who visited Berlin only after the wall fell but acutely remembers the anxiety of the Cold War.

“I remember fear,” said Enchelmayer, who also earned a master’s degree in speech and hearing studies from UNC in 1977 and works with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. She recalled crawling under her desk for school air-raid drills as a child. The fall of the Berlin Wall was in part an end to that fear.

— Beth Hatcher ’02