Converting The Shot

Posted on Nov. 12, 2018

Now she cuts down nets of her own. Charlotte Smith ’95 has willed the Elon Phoenix from perennial mediocrity to repeat champions. (Elon University photo)

Her stunning buzzer-beater put Carolina’s basketball program on the map in 1994. But it was Charlotte Smith’s losses that helped shape her into a winning head coach.

by Beth McNichol ’95

Charlotte Smith ’95 knows the question is coming.

She’s already spent part of a June evening in her Elon University office talking about the stuff that really matters: the lessons she’s learned since one improbable shot, a mere seven-tenths of a second in time, changed her life. How a win for the ages can turn into a long, expectant shadow, following you around for years after the last piece of confetti has fluttered to the court. How the world can shake you to your core, present death and divorce to you in a single year and dare you to keep your competitive edge, dare you to somehow grow from deep loss.

How, ever so slowly, Smith managed to do just that.

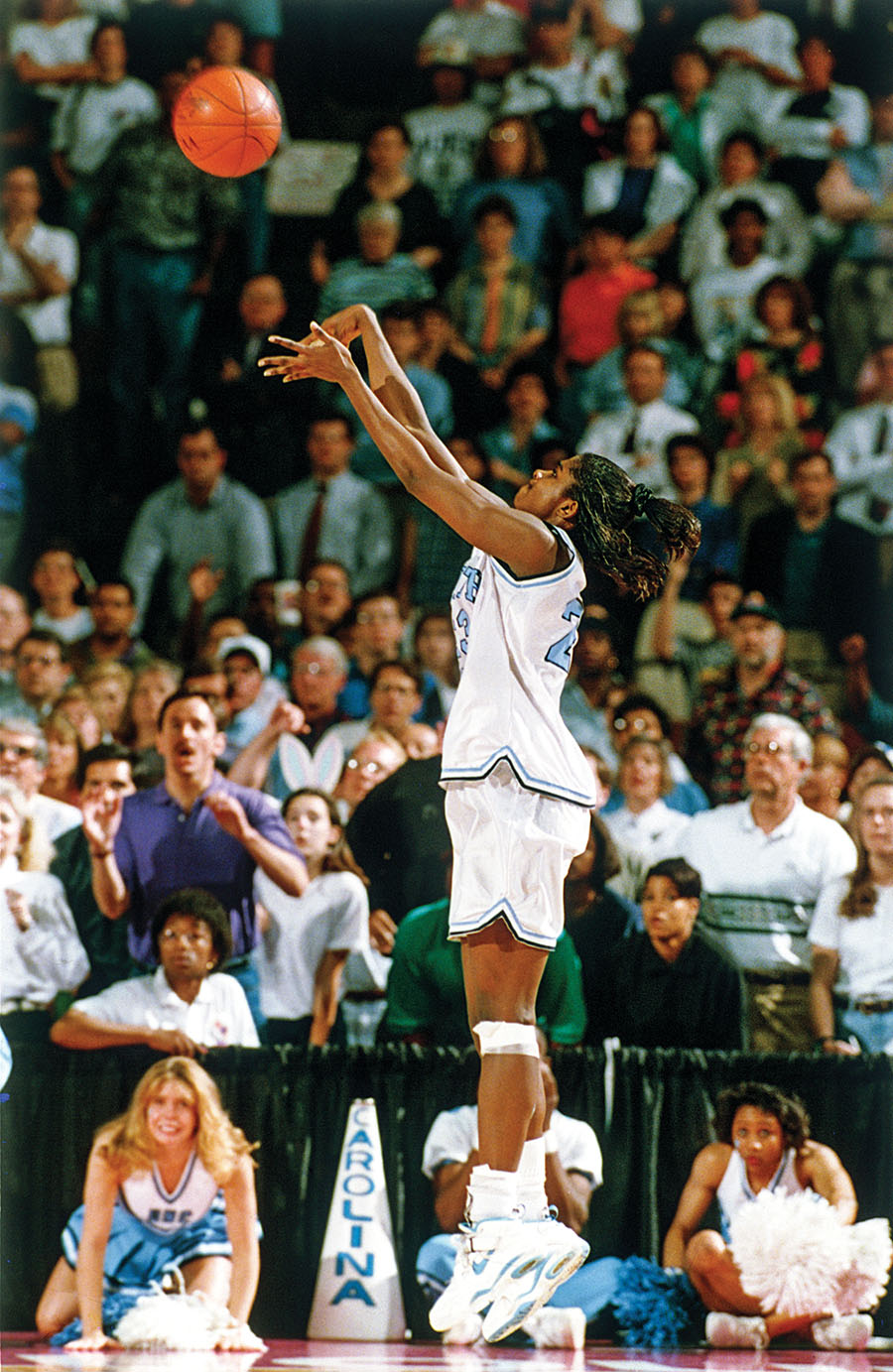

With seven tenths of a second left in the 1994 title game, Smith — who’d made only eight three-pointers all year — got the call. (Photo by Jim Gund/Getty Images)

And how the sum of those experiences helped turn the most-lauded North Carolina women’s basketball player of all time into a sought-after Division I head coach at age 45.

The truth is, the question of whether Smith will one day return to her alma mater to lead the basketball program that she lifted to its greatest heights 25 seasons ago — to its first and only NCAA title, on a breathtaking buzzer-beater — is a tiny part of her big life.

But the question is out there, on message boards and in athletics circles, because the sports world loves a good story about a homecoming, even if the story is still premature: Sylvia Hatchell is five years removed from a battle with cancer and finally looking in the rearview mirror at an NCAA investigation that implicated her team and caused star players to transfer — but ultimately led to no penalties. At 66, she’s in her 33rd season in Chapel Hill with two years remaining on her current contract. She insists she’s not going anywhere soon.

Still, Hatchell has been thinking about her legacy. Her active coaching tree extends to more than 40 branches now, and Smith, whose miraculous shot catapulted her program to success, blooms near the top.

“I’ve told people, I’ve said, ‘Look, she might take my place one day, you know?’ ” Hatchell said. “I mean, I’m not ready to retire yet — I want to coach a few more years and get the program back. But there’ll be a day. And nothing would please me more than one day, down the road, Charlotte would be the next coach here.”

With an endorsement like that, Smith has come to expect the question. And she answers it just like you think she will.

“All I think about,” she says steadily, “is the people who actually sign my checks, and that’s Elon University.”

The speculation that she might leave for a big-time program “has made my job pretty interesting here,” Smith said. “I’ve had recruits not come to Elon, because they said back in year two that I’m leaving. But it’s year eight, and I’m still here.”

“All I think about is the people who actually sign my checks, and that’s Elon University.”

–Charlotte Smith ’95

Smith’s response is not only prudent; it’s justifiable. Just down from her office at Alumni Gym on Elon’s leafy campus, the brand-new, 5,100-seat Schar Center waited to be christened by Smith’s team against Hatchell’s Tar Heels on Nov. 6. Since taking over at Elon in 2011, Smith has willed the Phoenix from perennial mediocrity to repeat champions. In 2017, Elon won the Colonial Athletic Association tournament title — the program’s first conference crown in Division I competition — and made its first NCAA tournament appearance in the 20 years since the school joined Division I. In 2018, Smith coached the sixth-youngest squad in the nation to a 25-win season and an upset victory in the CAA tournament over top-seeded Drexel. Off to the Big Dance went the Phoenix again.

Smith has gone 52-12 over the past two seasons, earning CAA and WBCA Regional Coach of the Year honors along the way.

She is beloved by her players, respected by administrators and deeply appreciated by the Elon community, who know they’ve found something special in Smith; season ticket sales to Phoenix games have increased 71 percent over the past three years, and attendance has more than doubled.

“I know with her success the last couple of years there have been some big schools, some Bowl Championship Series schools, that have been very interested in her,” said Hatchell, who talks frequently with Smith, offering advice. “I said, ‘Charlotte, look. Just because it’s a big-name school doesn’t mean it’s the right fit for you. If you go there, go for the right reasons.’ ”

So far, no one has been able to lure Smith away. At Elon, she says, she has everything she needs — a family atmosphere, a supportive administration and strong relationships. After years of chasing old shards of confetti, this is where she feels at home.

Searching for deja vu

If you haven’t watched the final seconds of the 1994 NCAA title game lately, make your way to YouTube now. You’ll be lifted by the sight of arguably the greatest clutch three-pointer in NCAA tournament history. With just seven-tenths of a second left, Stephanie Lawrence ’96 threads an inbounds pass under the basket and over Louisiana Tech defenders to Smith beyond the arc, who catches and shoots in what she later described as a dreamlike haze. Tar Heels win, 60-59.

Charlotte Smith ’95 hits arguably the greatest clutch three-pointer in NCAA tournament history.

The moment was extraordinary because of the do-or-die circumstances — in 2006, ESPN ranked it the most memorable moment ever in NCAA women’s play — but also because it was Smith who took the shot. Here’s a junior post player who had made only eight three-pointers all season, who had more rebounds (23, matching the then-record for tournament play) than points in the game, doing what she always did: completing her assignment. Smith was not the obvious choice, but she was the inspired choice to fool Louisiana Tech defenders.

Smith and Hatchell separately credited the same force for that gutsy call: divine inspiration.

“It had to be,” said Smith, “because who would pick me?”

Last April, Smith watched from a skybox at the women’s Final Four as Notre Dame’s junior guard Arike Ogunbowale hit a three-pointer from the same spot on the court to win the NCAA title. (The Fighting Irish had three full seconds on the clock for their final play.) Smith leapt out of her seat and sped down to the floor in search of a communal moment with Ogunbowale. “Because who else has done that,” she said, “besides me?”

When Ogunbowale and Smith finally connected, Ogunbowale, who didn’t know who Smith was, only had time for a quick, unfocused picture. The new heroine soon left for another interview, her story in the elite club just beginning. But Smith has lived her tale for the past 25 years, and here is what she might have told Ogunbowale:

First: Savor it, because the moment will disappear in a flash.

Second: Don’t keep chasing this feeling. Your career won’t always be like this.

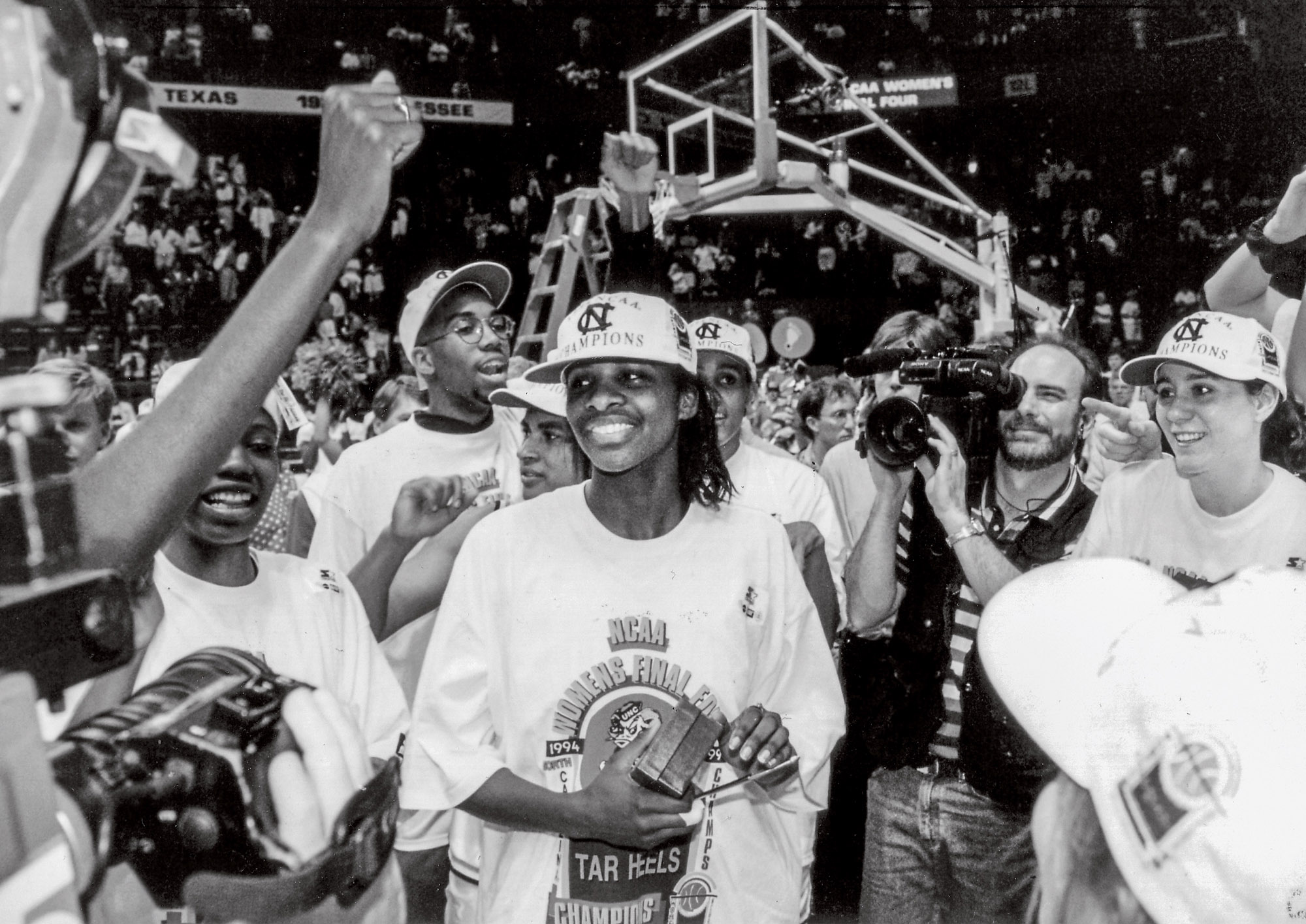

From the moment that she climbed out of the pile of euphoria that spread across the Richmond Coliseum in 1994, Smith felt the pressure of her achievement. (UNC Athletic Communications)

From the moment that she climbed out of the pile of euphoria that spread across the Richmond Coliseum in 1994, Smith felt the pressure of her achievement. When an ESPN crew came to town to film a reenactment of The Shot, Smith “took a million and one tries” to sink one like it.

Her senior year brimmed with personal accolades; she left Carolina as the most decorated UNC player of all time — the ESPN National Player of the Year, first-team All-America, the Most Outstanding Player of the Final Four, only the second woman ever to dunk a basketball in competition and the first Tar Heel woman to have her jersey retired. But what she remembers most from that season is losing to Stanford in the NCAA regional semifinals.

She continued to battle her expectations in the professional ranks, where growing pains collided with family tragedies and personal loss.

Smith joined the Colorado Xplosion in the now-defunct American Basketball Association in 1996. While helping Smith settle into her new life out west, her mother fell ill. Etta Smith, who was 47, succumbed to double pneumonia before Charlotte took the court for her first game. Smith pushed through a grief-stricken year to become the second-leading scorer and rebounder for Colorado’s conference championship team, only to be traded at the end of the season.

“I was really angry and bitter about the whole experience,” she said.

But if the beginning of her pro career brought tidal waves of emotions, the end of it, 10 years later, felt like a tsunami. Her 2002 marriage to attorney Johnny C. Taylor Jr. — the current chair of the President’s Board of Advisors on Historically Black Colleges and Universities, whom she met while playing with the WNBA’s Charlotte franchise — ended in 2006. Her father, Ulysses, died that June.

“[My dad] was the most dedicated and biggest fan I ever had,” Smith wrote in a letter to fans and teammates in December 2006. “I can’t imagine not seeing him in the stands anymore.”

Even in college, Hatchell recalled, “if she knew her parents were coming, Charlotte wasn’t worth a nickel until they walked in the gym. She saw them, and then all of a sudden, she just went to another level.”

Feeling smaller and more broken than she’d ever felt in her life, Smith retired at age 33.

Reminiscing in her office, where a poster of her iconic moment sits unframed and propped against the wall behind the door, Smith said she believed she could have kept playing if she had taken time off to grieve; she had posted her best WNBA seasons in 2004 and 2005, even while moonlighting as a UNC assistant in the offseason.

But a new perspective and the coach’s whistle awaited.

Caption: Smith in her Elon office. The Shot is never far away, but she learned “your career won’t always be like this.” (Anagram photo/Anna Routh Barzin ’07)

“When you reach that highest pinnacle of success, you want to keep reaching it, so you can feel the euphoria over and over again,” Smith said. “If you’re not careful to keep your perspective, you can become disillusioned and disappointed. And I found myself on that performance treadmill in the pros and just remember, every year, having this wish list of things that I wanted to accomplish in the WNBA. ‘I want to be an All-Star. I want to be a champion. I want to be this and that.’ And not reaching those milestones — and feeling like ‘less than’ because you didn’t.”

It can become a burden, an accomplishment like The Shot. “Especially,” Smith said, “when you allow it to become your identity. In reality, it’s what you do, but it’s not who you are.”

Preacher, poet, healer

Even after nine years by Hatchell’s side at UNC, learning to manage a Division I program, Smith wasn’t sure she was ready for the training wheels to come off. No one ever is, she said. She’d interviewed for head coaching positions, and the rejections — always over her lack of experience as a head coach, an obvious if unconstructive criticism — were starting to fray her confidence.

“Doubts creep up. You start to ask yourself if you have what it takes.”

So when Elon Athletics Director Dave Blank called in summer 2011, Smith panicked and threw the phone down on her bed, letting the rings die out unanswered. This was it.

“I can’t answer it,” she said. “I can’t answer it.”

But Hatchell knew she was ready. Smith’s mentor had spent more than an hour on the phone with Blank during the interview process, singing Smith’s praises. “She’ll make you look good,” Hatchell had told him.

After Smith summoned the courage to redial and accept the job, Elon quickly found that Hatchell was right. The earliest proof came not on the court but at an intersection in Burlington in 2011.

Smith had been allowing drivers who were exiting a tricky Chick-fil-A parking lot to reenter the congested highway in front of her car. She was stopped at a red light when a man behind her got out of his vehicle, approached her window and stood in front of her, repeatedly screaming, “N—–s gotta get out of the way.” Smith said she never before had experienced such direct, stunning racism. She shook all over but managed to turn toward the man, who was white, and respond, “God bless you,” after each insult.

On the way to the police station to report the incident, she called Blank, then returned home to decompress. For Smith, a devout Christian and ordained minister whose father was a bishop, that meant writing — poetry, sermons and music. When she returned to her office, a squad of administrators that included the university president were waiting to offer their support.

“What can we do?” they asked.

She handed them the lyrics and music to a gospel song she had just completed, titled Lord Give Us Your Heart.

“Could you help me get this song produced?” she asked.

At a time of great tension in our nation, Charlotte Smith offered a message of peace.

Elon enlisted a music professor to arrange the piece and a gifted Elon choral student to sing it. In January 2015, as stories of police brutality in the African-American community roiled the nation, Smith recorded an introduction to the song in which she spoke of the traffic incident. Elon posted the video on YouTube and other social media.

“At a time of great tension in our nation,” Smith said calmly into the camera, “I would like to offer a message of peace.”

That, say her friends, is the essence of who Charlotte Smith is today. Not the player who sank The Shot. Just a woman who believes that her faith in the world is transferable, who counts to eight before she lets people go from her hugs.

“Her mom and dad were really warm and caring,” said Tonya Jackson ’96, a member of the 1994 championship team and a school counselor in Durham. “She had a good foundation to draw from. But all that was strengthened [through her own hardships] because she wants people to feel important and valued.”

Smith has visions of opening the Charlotte Smith Dream Center one day, a place where kids can come and find themselves through music, art, writing and sports. She’s written a book of devotionals for coaches and is working

on a second one for players. She posts pop-up sermons on her public Facebook page. She guest-ministers at neighbors’ churches. She worries about the quietly bleeding hearts around her, the loneliness that lives beyond her sight.

“I know from my own experience of brokenness,” she said, her voice softly cracking, “having gone through divorce, having lost my mom and dad, suffering through a lot of loss, that it changes you.”

“She’s never going to be satisfied. She’s not thinking, ‘Oh, we made it to the tournament last year and played a close game; we’re good right here.’ She wants to go deeper in the postseason, dominate the lead more. She’s grown and grown in confidence as a coach.”

–Elon Assistant Coach Josh Wick ’01

Hatchell has always said that you couldn’t combine Smith’s athleticism with her competitive nature and not find an All-American stirring beneath. But Smith’s vulnerability creates her strength as a coach. She conjures the most humbling moments of her own life to inspire the greatest response in her players.

“She’s good at reminding you to take a step back and see the bigger picture in life,” said Samantha Coffer, a former Elon player who is now a third-year medical student at Carolina. “She talked about going from being a superstar in college to riding the bench early in the WNBA, and how that was a challenge for her. She liked to say that you can get bitter or you can get better.”

She’s still hard on herself. She dissects game film like a surgeon wielding a scalpel and forces herself to take deep breaths before she debriefs her team. She wrinkles her nose as she admits she would’ve liked to have won a conference title by year five, not year six. She must remind herself still that a loss is just a loss, not a failure.

“She’s never going to be satisfied,” said Elon Assistant Coach Josh Wick ’01, who’s known Smith since she was a UNC assistant coach. “She’s not thinking, ‘Oh, we made it to the tournament last year and played a close game; we’re good right here.’ She wants to go deeper in the postseason, dominate the lead more. She’s grown and grown in confidence as a coach.”

Although once she may have worried about disappointing Hatchell or other mentors, Wick said, she no longer does. She owns her team, owns her job, owns the results — and each year those results, on and off the court, get a little bigger.

“It’s teaching them the importance of selflessness, the character traits that transfer,” said Smith, who was a North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame inductee in 2015. “That’s what I have to get them to open their eyes and see, that what they’re learning is so much bigger than basketball. Like, when you’re married one day, you’re going to need to know how to be selfless and sacrifice, that it’s give and take. And it’s not just about me.”

Much has changed since Smith first arrived at Elon. Her players no longer make spring break plans; they assume they will be playing in the NCAA tournament. Seven years ago, the athletes Smith recruited had no idea who she was. Now, says Wick, “they may not know everything she did as a player — but they do know her as Coach Smith at Elon.”

She’ll take that identity. Shay Burnett, who left Elon last year as a three-time all-conference honoree, once wanted to dunk like Smith. Now, she wants to coach like Smith.

“If you’ve met her,” Burnett said, “she’ll change your life.”

When Elon announced its new coach seven years ago, Burnett, who is from nearby Graham, was still just a teenager being recruited by the school. She didn’t recognize the name that had launched an on-court frenzy in 1994. But Burnett’s parents did. Her parents knew it all: the competitiveness, the dunk, the championship. The Shot. They knew how divine inspiration, a fraction of a second in time, could alter a person’s life.

“Coach Smith has done everything you want to do,” they told their daughter. “She’s the one.”

Beth McNichol ’95, a freelance writer based in Raleigh, is a former associate editor for the Review.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.