Honest Abe at the GAA

Posted on May 2, 2023In 1972, while browsing in a small antique shop in Hillsborough, John Short ’71 happened upon a bronze mask of Abraham Lincoln. It was made from a plaster mold created a few months before the 16th president’s assassination. Still, it’s commonly referred to as Lincoln’s death mask.

Short, 24 at the time, was instantly smitten with the mask but couldn’t afford its $5,000 price tag, which he says back then could purchase two Toyotas.

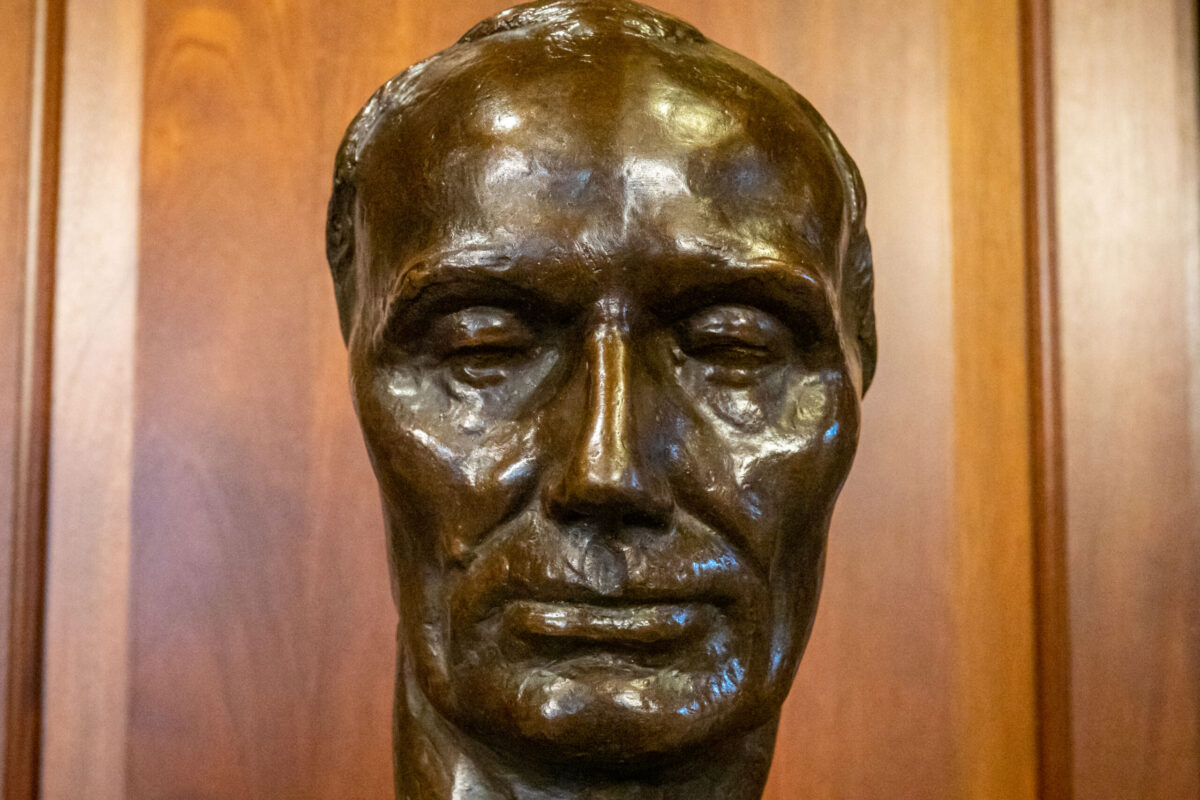

The first bronze Lincoln mask, which captures his face before he grew a beard, was unveiled in November 2019 at The Lincoln Forum in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, home of his famous 1863 address. (Photo: GAA/Cory Dinkel)

Even still, Short said the Lincoln mask never left his thoughts, almost haunting him in a way. Two decades later, in 1993, he attended an art auction in Pasadena, California, looking for paintings. When a life-sized, terra cotta sculpture of Lincoln’s face unexpectedly came up for bid, Short sat anxiously in his seat, hoping somehow, this time, he could swing the asking price. The terra cotta had been created by famed sculptor Robert Merrell Gage, who was the favorite protégé of Gutzon Borglum of Mount Rushmore fame and created many public statues, including the seated Lincoln at the Topeka, Kansas, Statehouse grounds. In 1860, sculptor Leonard Volk used plaster on Lincoln’s face to replicate his bone structure. After Volk died, Gage came into possession of a copy of the mask, which he used to hand create a clay sculpture of Lincoln’s face — which is what Short saw at the auction.

“I fell in love with it instantly and wondered secretly whether I’d be able to bid against these people with all this money,” Short recalled. “The fates brought it back to me. My bid won, and I carried it home on the plane wrapped like a little baby.”

Today, 30 years after Short bought the terra cotta, a bronze of Lincoln made from it sits inside the Johnston Room of the George Watts Hill Alumni Center. Short and his business partner Clell Hamm ’92 donated it this year to the GAA. They’ve known each other since Short was a Carolina student working in Hamm’s parents’ motorcycle shop. The men formed the 1865 Club, named for the year Lincoln was assassinated. Members own bronze masks made from the mold as part of what they call The Face of Lincoln Project. At the time of their Review interview, the men had made 45 bronze masks. Priced at $9,900 each, they’re sold by the N.C. Gallery of Fine Art in Wilmington, which Short and Hamm founded.

Short bought the original terra cotta but quickly points out the project would not have come to fruition without Hamm. “If it’d been left up to me, it’d still be in my bedroom as a terra cotta,” Short said. “Clell had the business acumen and expertise to make this all happen.”

Though Hamm had seen the terra cotta at Short’s home many times, it wasn’t until 2017 that they decided to make the first bronze. That year, it dawned on Hamm that the poignant expression Gage captured — with Lincoln deep in thought — “was something that needed to be shared with the world.”

Clell Hamm ’92, left, and John Short ’71 donated this Lincoln bronze to the GAA. (Photo: GAA/Cory Dinkel)

From the outset, they had questions. Was the terra cotta copyrighted? Did they have the right to produce a bronze from it?

Short introduced Hamm, who owns a hearing aid business in Wilmington, to Ed and Melissa Walker, who had restored a painting for Short. Melissa Walker is a certified art educator. Ed Walker owns Carolina Bronze Sculpture, an internationally known fine art bronze casting foundry in Seagrove.

Ed Walker told Hamm he could make a bronze of the terra cotta, and from that point, Hamm and Short began strategizing to produce and sell the bronzes.

The first bronze Lincoln mask, which captures his face before he grew a beard, was unveiled in November 2019 at The Lincoln Forum in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, home of his famous 1863 address.

Later, Hamm and Short met officials at the Lincoln Memorial Shrine in Redlands, California, who were interested in purchasing the bust that had been unveiled at the forum. They said it was special to sell the bronze sculpture to the shrine because Gage had designed the fountains there.

It takes a team of 12 to 15 artisans almost four months to produce a Lincoln mask. The first step involves making a wax mold from the terra cotta. The mold is then dipped into a silica, placed upside down in an oven and heated to 2,200 degrees, melting the wax. After about an hour, handlers, wearing “space suits” for heat protection, remove a hollow two- to three-inch-thick cocoon from the oven.

A small crane tips a kettle of molten bronze, pouring the lava-like liquid into the cocoon mold. After it cools for several hours, large hammers are used to break the thick outer cover to reveal the bronze face, which emerges silver in color. Handlers then sandblast the bronze and heat it with a blowtorch. Later, a mixture of chemicals is applied to produce the final bronze color before polishing.

“When you live with the bronze like I have now, and John lived with the terra cotta, you feel like you have a deeper appreciation for Lincoln, almost like he’s become a friend,” Hamm said. “Obviously, we all appreciate Lincoln … so you want to model him in many ways.”

The mold’s the same for each bronze, yet each is individually finished. The first Lincoln bronze went to Hamm, and the second went to Short. Hamm said bronzes have been purchased by people from all walks of life. Short said the project has “come full circle” from that day in the Hillsborough antique shop when he held the death mask, and he and Hamm “can’t wait to see where it leads us.”

— Laurie D. Willis ’86

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.