The Healer

Posted on Sept. 12, 2019

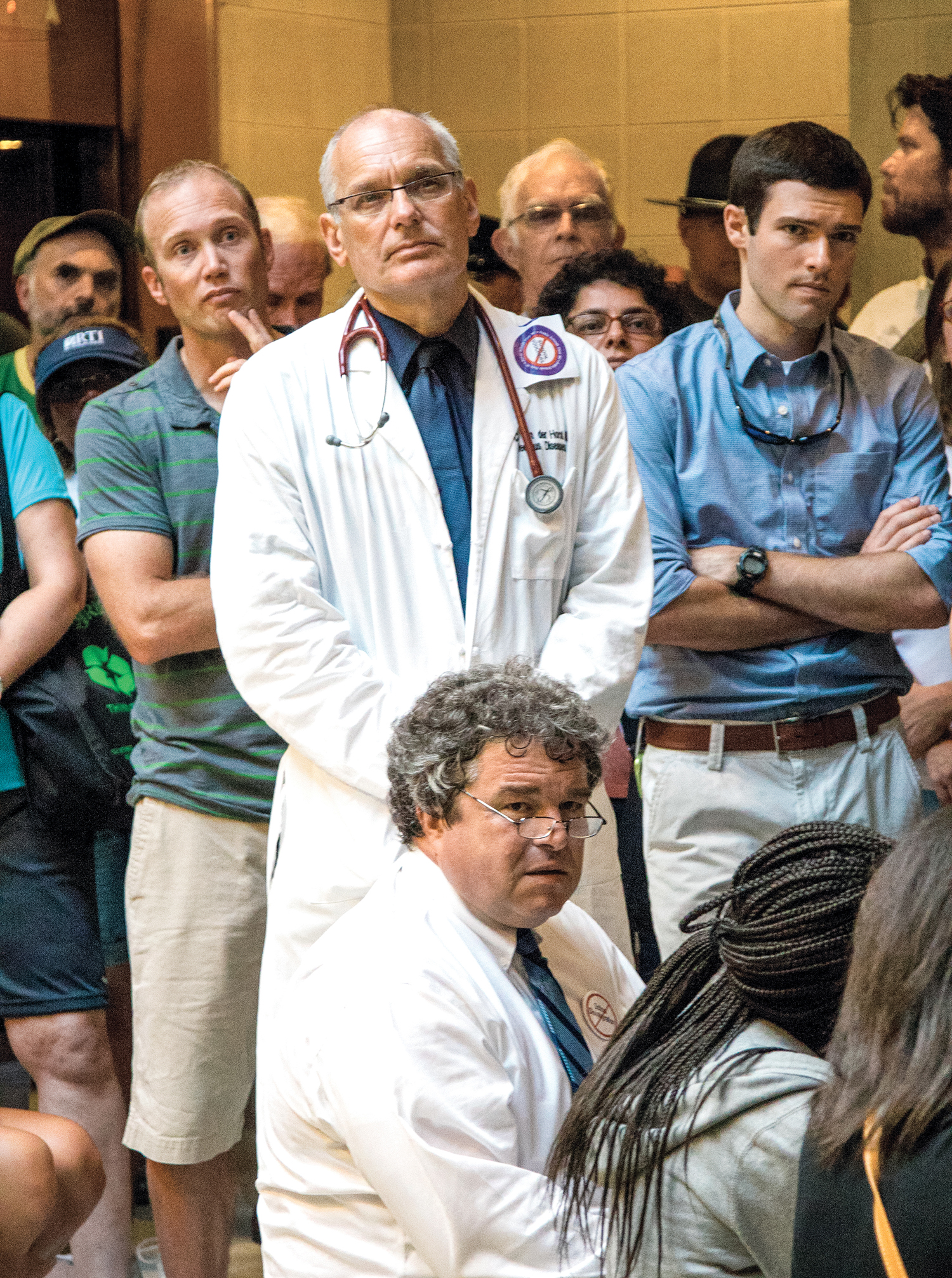

Charlie Van der Horst, center right, protesting the N.C. General Assembly’s refusal to expand Medicaid. (Photo by Phil Fonville)

Charlie van der Horst cried and laughed with equal passion. The pioneering AIDS doctor, social justice apostle and consummate caregiver leaves a storybook legacy.

by Barry Yeoman

The more than 100 activists who converged on North Carolina’s Legislative Building in May 2017 stood listening to a retired UNC physician in a white lab coat. He was tall, in his mid-60s and spoke in a nasal voice that hinted at his family’s Eastern European origins. A broad red ribbon was tied around his left sleeve, signaling his intention to be arrested.

Dr. Charles van der Horst was a leader in the state’s Moral Monday movement: a doctor who could explain, precisely and passionately, the consequences of the Legislature’s refusal to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. The expansion, funded almost entirely by federal dollars, would have covered at least 300,000 North Carolinians. Without it, studies suggested, more people would die.

To van der Horst, political protest wasn’t just compatible with the practice of medicine; it was essential. He was an internationally recognized scientist who had headed UNC’s HIV/AIDS clinical trials unit. His research on two continents had saved innumerable lives. But on that afternoon in Raleigh, addressing his fellow activists, van der Horst focused on the patients whose suffering he couldn’t alleviate.

One was a young woman who had felt a mass in her breast but, because she had lost her job and insurance, didn’t seek care. “By the time she arrived at our clinic, she had widespread metastatic breast cancer,” he said. Another was a fast-food worker who couldn’t afford high-quality insulin to control his diabetes. “He’s going blind, and half of his kidney function is gone, and he likely will have an early death, joining 1,000 people a year who die in North Carolina for want of Medicaid expansion.”

“Shame!” the crowd chanted.

Van der Horst, at top left, listens at a Moral Monday protest in Raleigh in 2013. The protests were, for him, the culmination of a lifetime of activism — as a child he marched for civil rights with his father. At bottom left is author Tim Tyson, a friend who comforted him during a traumatic arrest. (Photo by Jenny Warburg)

When police tried to disperse the protesters, van der Horst didn’t leave. Instead, he offered his own body in exchange for those he couldn’t heal. Officers cuffed his wrists in plastic zip ties and led him, with 31 others, to waiting vehicles.

When he reached the van, the bravura that fueled van der Horst’s oratory began to drain. It was dark and cramped inside, with a low ceiling, and the arrestees sat on metal benches. Van der Horst thought about Freddie Gray, the Baltimore man who had died in 2015 of injuries he sustained in the back of a moving police van. He grew scared.

Until then, “everybody was in pretty good spirits,” said Tim Tyson, an adjunct professor of American studies at UNC who also was arrested that day. “But suddenly Charlie’s face went dark and he began to weep.” The physician explained that his mother had survived the Holocaust: In Nazi-occupied Poland, she had been beaten with a soldier’s rifle when she refused to leave the basement of an apartment building where she was hiding. After she recovered from the attack, she returned home to find her mother gone and her father and sister killed.

“I started feeling panicky,” van der Horst later recalled of that day in Raleigh. “The way the Nazis initially gassed Jews was to put them in the back of vans and pipe in the exhaust.”

Tyson noticed his friend’s distress. He considered the depth of van der Horst’s sensitivity: how it could embolden the doctor to speak out for his patients and then, in a moment, flip around and trigger his terror. Tyson moved down the bench, took van der Horst’s zip-tied hand in his own and held it until the moment passed.

Ferocious affection

Van der Horst, who died in June, always ran toward intensity. He took on AIDS care in the 1980s, when the disease was still mysterious, and later brought his research to sub-Saharan Africa. He used his physician’s authority to throw a wrench into the state’s use of the death penalty. At Moral Monday events, he stood beside the Rev. William Barber II, former president of the state NAACP, and accused lawmakers of having “blood on their hands.”

He lavished the people around him with ferocious affection: close friends, not-so-close friends, co-workers, comrades, mentees. He hugged and kissed without regard for gender or social convention. “Charlie had an emotional flamboyance and demonstrativeness that can be confusing to people that are trying to pigeonhole your sexuality,” said his friend Cheryl Marcus ’81, retired clinical research director of the clinical trials unit.

He loved to celebrate virtually anything. “Enrolling the first person in a difficult-to-recruit-to research study? He wanted to throw a party,” Marcus said. “Getting a good grant score? There needed to be a party.” At national meetings, he hosted dinners at which he praised the accomplishments of individual colleagues. “He always included everyone,” Marcus said. “And he always cried.”

Van der Horst, who died in June, always ran toward intensity. He took on AIDS care in the 1980s, when the disease was still mysterious, and later brought his research to sub-Saharan Africa. He used his physician’s authority to throw a wrench into the state’s use of the death penalty. At Moral Monday events, he stood beside the Rev. William Barber II, former president of the state NAACP, and accused lawmakers of having “blood on their hands.”

An accomplished athlete, van der Horst swam prodigious distances. “Racing 15 miles in the Hudson River beneath the cliffs of West Point, dwarfed by an oil tanker with its propellers moving whump, whump, whump like some whale in heat, brought perspective as to the vastness of nature,” he wrote in 2018. Tossed around by the waves, “I embraced the calm knowledge that I could ride them out despite my primal fears of the immense crushing power.”

It was in the Hudson River that van der Horst died June 14. He drowned during what his family describes as an apparent heart attack. He was participating in a weeklong, 120-mile swim from the Catskill Mountains to New York Harbor. He was 67.

The path back to faith

He chose his specialty because he didn’t want to lose patients. “I loved oncology, but I thought, ‘Oh golly, they all die,’ ” van der Horst told writer Jonathan Michels ’11 in an interview housed in UNC’s Southern Oral History Program. “I couldn’t hack that. I would just be too sad all the time.” He decided instead to concentrate on infectious diseases. “And I’ll just take care of little old ladies with pneumonia and make them better.”

That was 1981, when he was at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx before he began a three-year infectious-disease fellowship at N.C. Memorial Hospital and Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Research Center. It was the same year that the government identified clusters of gay men with a rare lung infection called Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and an aggressive cancer called Kaposi’s sarcoma. It would take another three years for scientists to identify HIV as the virus that causes AIDS, and longer for the first effective treatments to surface. In the meantime, van der Horst began caring not for “little old ladies” but instead for young, terminally ill adults.

It was a shattering introduction to medicine that shook his spiritual foundation. After World War II, van der Horst’s mother had wondered how a loving God could have permitted the Holocaust. Confronted with AIDS, he wondered the same. At synagogue each week, he praised God in a silent prayer called the Amidah. “But in the crisis, I would stand up and it was all meaningless to me,” he once said. “The words were like dust.” (The interview was published in the 2000 book AIDS Doctors: Voices from the Epidemic.)

Nonetheless, he pitched himself into the work. Linda Belans, a writer and leadership coach, was friends with van der Horst’s first patient, Nat Blevins Jr. ’85 (MEd). Early on, Blevins felt like a pariah. “The doctors would stand at the doorway and talk to him in his bed,” Belans recalled. “When they would come near him, they’d glove up.” By contrast, “Charlie put his hands on him. He sat next to him on a chair, and he listened to his stories.”

For van der Horst, human contact was a path back to faith. “I experience the simultaneous pain and joy of being able to articulate and speak with Nat and hug him and kiss him and express my doubts about being his clinician — that I don’t know if I’m capable of making unbiased decisions to help him,” he recalled. “And him saying, ‘That’s OK: That’s why I want you to be my doctor.’ So in a sense, then, I think I was able to find God again.”

Van der Horst with Clifford Mayes Jr., an HIV patient, in the Infectious Diseases Unit at UNC Hospitals. He chose his specialty over oncology, then studied it at UNC. (Photo by Harry Lynch/News & Observer)

Breakthrough in Malawi

Van der Horst returned to UNC in 1988, after stints at Duke University and Research Triangle Institute. The clinical trials unit he headed helped develop the antiretroviral drugs that, starting in the ’90s, turned HIV from an automatic death sentence to a serious but manageable disease.

But van der Horst is better known for his later work with UNC Project Malawi, where he and his colleagues tackled the issue of mother-to-infant transmission in one of the world’s poorest countries.

Mothers with HIV can pass on the virus through breast milk. But babies in the developing world who don’t breastfeed risk malnutrition and a host of diseases, including fatal diarrhea from contaminated water. Van der Horst led studies that showed women with HIV could safely nurse if they, or their infants, took certain antiretroviral medications.

The Malawian government used the findings to craft its own prevention program in 2011. Since then, mother-to-infant transmission has plummeted so much that UNC Project Malawi now has trouble recruiting young subjects for its HIV cure studies. “We can’t find any infected kids,” said Mina Hosseinipour ’04 (MPH), the project’s scientific director. “That’s how much the landscape has changed.”

Based partly on the Malawi research, the World Health Organization issued a series of recommendations that women with HIV continue to breastfeed while they, or the babies, take antiretroviral drugs. “It changed the course of HIV, certainly for mothers and infants around the world,” said Dr. Pierre Barker, head of global operations at the nonprofit Institute for Healthcare Improvement and a clinical professor at UNC’s Gillings School of Global Public Health.

“He exasperated me. He embarrassed me. He wasn’t always socially correct. But whether he was fighting for compassionate care of people with HIV or bringing a groundbreaking clinical research study to one of the poorest countries in Africa or fighting for Medicaid expansion, he roared from the heart, and that heart had a moral compass that was true and unwavering.”

— Cheryl Marcus ’81, a friend and retired research director of the clinical trials unit

Even as he was winning international recognition, van der Horst was midwifing the next generation of public health researchers. Dr. Bhakti Hansoti, a young physician, applied for a Fogarty Global Health fellowship to help prevent children from dying in South African emergency rooms. (Van der Horst helped administer the fellowship.) “It was a bad application,” she recalled. “I had no idea what I was doing. Charlie painstakingly helped me rewrite my whole proposal so that I would have a fighting chance.”

After she won the award, Hansoti went through a divorce and depression — “the kind of stuff that ends your career,” she said. “I was really transparent with Charlie: ‘I’m not in a good mental health place. I don’t know I can do this.’ ” Van der Horst pushed back, asking her, “Can you think of a better place to go and heal?” He continued to mentor her after the fellowship — “for no obvious reason, no gain for him, just because he saw some sort of spark.”

Through it all, he never stopped treating patients. His clinical work grounded him in daily reminders of the lives at stake. “Many of us in academia divorce humanity from the data,” said Greg Millett ’95 (MPH), director of public policy for amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research. “Charlie ignored the barriers that his profession set up. And it made his science, and his clinical work, that much more impactful, because he refused to sit back and be dispassionate.”

The tireless activist

Moral Mondays, for van der Horst, were the culmination of a lifetime of activism. His parents, who emigrated with him from the Netherlands in 1952, saw a connection between European fascism and Jim Crow segregation, and as a child he marched for civil rights with his father. He was raised to equate defiance and survival, just as his mother refused to board a Nazi train in World War II. “She said to the individual SS man, ‘Shoot me here if you want to kill me, but I’m not going out of this basement,’ ” he said during a 2014 interview. “And he backed down and left.”

A frequent speaker at Moral Monday rallies, van der Horst was twice arrested for civil disobedience at the events, here in 2013. He offered free medical advice to the activists, who embraced him. (Photo by Travis Long/News & Observer)

During medical school, van der Horst protested what he viewed as undue influence from drug companies and unethical research on pregnant women. He saw advocacy as part of his role as a physician: addressing the bigger issues that keep his patients, or anyone, from living healthy lives. In 2007, he and some colleagues successfully lobbied the N.C. Medical Board to threaten sanctions on doctors who monitor executions. “We don’t kill patients,” he told CBS Evening News. “That’s the bottom line.” Although two courts later ruled that the board had overstepped its authority, North Carolina hasn’t executed a prisoner since.

Occupying the Legislature during a 2013 Moral Monday protest felt like a natural progression. Of all the Republican majority’s new policies, the rejection of Medicaid expansion hit van der Horst most directly. “We all believe in a certain set of principles that should govern a society,” he said. When legislators violate those principles, “we need to speak out, stand up and call them for what they are. And that is immoral.”

Van der Horst was arrested twice, in 2013 and 2017. He was a regular speaker at Moral Monday rallies. He offered free medical care to activists, both in public and in private. (He once showed up at labor organizer Keith Bullard’s home and volunteered to help him compose a will. After Bullard grasped the doctor’s message, they worked together to get Bullard’s diabetes under control.) And he became a beloved part of that community.

“He was angry about what was happening to people,” said Yara Allen, a leader in the advocacy group Repairers of the Breach. “But Charlie was the first to dance when the band was playing. It wasn’t that we were so much celebrating. We were releasing energy and refueling, getting love and energy from each other.”

Also in need of healing

Van der Horst’s friends urged that he not be portrayed as a saint. He got distracted. He lost his temper. His confrontational style alienated some of his colleagues.

He also hid, even from loved ones, what he called the “black fog of depression” that plagued him before his 2015 retirement. He suffered post-traumatic stress from the AIDS epidemic. He couldn’t sleep, and when he did he had nightmares. He drank too much. He stopped wearing a seatbelt. He scouted out a place to make a six-story leap.

When he finally told his wife, daughter and friends, they “encircled me with a protective and patient healing love,” he wrote in a 2018 newspaper column. He sought out talk therapy, anger management lessons and medication. And he decided to retire from UNC. Although he defined himself by his work, he wrote, “I realized that leaving my job as an academic physician was a key part of my recovery.”

Friends describe that column, published in The Herald-Sun of Durham, as another act of generosity. “He exposed his vulnerability because he thought it might help others,” said his friend Carla Fenson ’95 (MEd), an early-childhood consultant.

That imperfect van der Horst is the man his friends miss.

“He exasperated me. He embarrassed me. He wasn’t always socially correct,” Marcus said. “But whether he was fighting for compassionate care of people with HIV or bringing a groundbreaking clinical research study to one of the poorest countries in Africa or fighting for Medicaid expansion, he roared from the heart, and that heart had a moral compass that was true and unwavering. Even if you lagged a few steps behind, in the very large shadow he cast, you could be assured you were on the right path.”

Barry Yeoman is a freelance writer based in Durham.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.