The Little Slide Show That Could

Posted on Nov. 12, 2021

Caribou antlers hanging on wooden racks, Old Crow, Yukon, 1988, from Lenny Kohm’s Last Great Wilderness show. (Photo by Lenny Kohm)

Historian Finis Dunaway ’93 tracked one man’s efforts to save Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and learned the power of trickle-up environmentalism.

by Andrea Cooper

Finis Dunaway ’93 had never crashed a memorial service before. He slipped into a seat near the back of the community center at the base of Grandfather Mountain in North Carolina. The place was packed on a sunny fall day, with more than 100 people gathered to honor the life of an environmental activist named Lenny Kohm. One of Kohm’s friends had invited Dunaway and assured him, “Lenny would want you to be there.” Still, Dunaway “definitely felt awkward,” wondering if he belonged at a remembrance for someone he didn’t know.

Finis Dunaway ’93

Scanning the room, he took in the artifacts on display of Kohm’s life:

A camera Kohm likely used to shoot photos of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the unspoiled yet contested land in the northeastern corner of Alaska. Two slide projectors he toted around the United States with a slide show to encourage audiences to save the refuge from oil drilling. A beaded caribou-skin vest, a gift from friends among the Gwich’in people, who depend upon the refuge’s Porcupine caribou herd for their way of life.

Dunaway was in a good position to make mental notes about it all as a professor of history with particular expertise in visual culture.

For the next 90 minutes, Kohm’s friends and colleagues shared tales of an eccentric Jewish man who brought a playful sense of humor, nonstop passion and an innate brilliance for strategy to his work as a grassroots organizer. The crowd, which included former lobbyists for major environmental groups and a leader from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, burst into laughter often.

But the speaker who had the greatest impact on Dunaway was Luci Beach, a Gwich’in woman who had come from Alaska on behalf of the Gwich’in nation. She had traveled years ago with Kohm on his multimedia slide show tours to inspire Americans to preserve the refuge. Now she teared up as she described a man who respected Gwich’in people as individuals, who knew environmentalists should not vow to save pristine wilderness while ignoring the people who depend upon it for their lives.

“If it wasn’t for Lenny,” she said, “I really think there would be drilling in the Arctic Refuge right now.”

Dunaway listened, intrigued but skeptical. Beach’s praise might be kindhearted hyperbole. Was it really possible for a white environmental advocate to form a bond with an Indigenous community that wasn’t merely transactional for his own ends? Maybe, Dunaway thought, that analysis was more a projection “of what they wished the connection was.”

Besides, how could an old-school slide show make that much difference in one of the biggest environmental debates of our time?

Dunaway would spend the next five years finding out. It wouldn’t be easy. He was sitting at the memorial service for the man who held many of the answers.

The power of images

Before he became a professor at Trent University in Ontario and a leading scholar on how environmental images shape our history, Finis Dunaway was a kid from a conservative family in Mobile, Ala., where his mom worked as an accountant and his dad sold insurance.

Finis (rhymes with Linus) is a family name given to his father and grandfather before him. The story behind it? A friend of the family was the last of 13 children. His parents named him “Finis,” the Latin word for “the end.”

“But it’s Alabama,” Dunaway explained, adopting the Southern drawl of his youth, “so it’s ‘Fine-us.’ ” Dunaway’s ancestors decided they liked the name, too. “I tell people it’s a good form of birth control because I’m an only child.”

Even in his conservative community, people were moved by the photos of blackened beaches, dead sea otters and oil-soaked birds following the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska in 1989. They weren’t anti-fossil fuels but maybe anti-Exxon, Dunaway said. “That shows you the impact of media images on the public.”

“Historians typically use images only as illustrations of the past, as mirrors of what happened. … They tend not to think of images of having this active role to play in the past in shaping public attitudes and really being part of history.”

— Finis Dunaway ’93

The images were one inspiration for his interest in environmentalism at Chapel Hill, where he joined Carolina’s chapter of the Student Environmental Action Coalition. He heard a “who’s who of the environmental movement” at a student-led, national conference. He spent two summers going door to door across the Research Triangle to talk about environmental issues, particularly strengthening the Clean Air Act. Other social justice interests also came calling when he played a small role in an organizing campaign for the housekeepers at UNC.

He flirted with becoming an environmental attorney early in college, but Dunaway grew more critical of environmentalism as graduation neared. It was, he thought, “a little too focused on affluent people, on green consumerism as an answer to solving problems, and somewhat detached from issues of social justice.”

He flirted with becoming an environmental attorney early in college, but Dunaway grew more critical of environmentalism as graduation neared. It was, he thought, “a little too focused on affluent people, on green consumerism as an answer to solving problems, and somewhat detached from issues of social justice.”

But in graduate school at Rutgers, where he had planned a PhD in history focused on working-class labor movements, he couldn’t shake the pull to engage with the environment. He started to see environmental history as a way to understand the past. He read accounts detailing the effects of colonial capitalism on the ecosystem, among other works. Before then, Dunaway “had no idea that historians would take nature as a category of analysis and that the environment was part of what a historian would consider.”

What’s more, he realized images could create history, not just reflect it. “Historians typically use images only as illustrations of the past, as mirrors of what happened. They either use them as ornaments to the prose — ‘oh, here’s a nice little picture to slap in there’ — or as objective evidence,” Dunaway said. “They tend not to think of images of having this active role to play in the past in shaping public attitudes and really being part of history.”

That realization has been a constant theme in his work since his first book in 2005, Natural Visions: The Power of Images in American Environmental Reform, and his second in 2015, Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images.

Seeing Green, and a column he wrote for The Chicago Tribune, earned his research widespread attention and inspired part of a segment in March on HBO’s Last Week Tonight with John Oliver on why recycling isn’t the solution for plastics.

Snow Geese I, Jago Riuer Valley, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, 2002, by Subhankar Banerjee. Dunaway credits this photo with sparking his fascination with Alaska’s 19-million-acre refuge.

In the Tribune op-ed, Dunaway wrote about the famous “Crying Indian” anti-litter ad, familiar to anyone who watched U.S. television in the 1970s. Iron Eyes Cody (in reality an Italian American actor) sees trash strewn on the landscape and cries one tear as a voiceover intones, “People start pollution. People can stop it.” The ad was funded by Keep America Beautiful, a collection of beverage and packaging corporations “staunchly opposed to many environmental initiatives,” Dunaway writes in the op-ed.

Those corporations wanted to shift responsibility for pollution from themselves to individuals, Dunaway wrote. Litterbugs were the problem, not the throwaway containers destined for landfills. The corporations also opposed legislation that “would require soft drink and beer producers to sell, as they had until quite recently, their beverages in reusable containers.”

The piece is one of Dunaway’s most-read essays, and Kathryn Morse, a professor of history and environmental studies at Middlebury College in Vermont, said Seeing Green is a popular text among her students. Students “immediately understand” that the Iron Eyes Cody ad is meant to evoke guilt.

In an era when our senses are overrun with stimuli, from social media to streaming to gaming, Dunaway’s work sheds light on how we’ve interacted over time with images, both moving and still. Andrew Kirk, professor of history at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, said Dunaway is in “a select group of distinguished scholars of visual history. He is a master interpreter of visual culture and has an eye for important histories not visible without his methods.”

That same careful eye caused Dunaway to stop, entranced, in front of a promotional poster bearing an image of the Arctic by the acclaimed photographer Subhankar Banerjee in 2005. Alternating bands of orange and blue, of flat land and luminescent waters, all led to the Beaufort Sea, part of the Arctic Ocean. Gazing more deeply, Dunaway realized the image showed thousands of snow geese in flight, like waves moving toward the horizon.

Dunaway acknowledged that partisan politics now pose more significant challenges than they did in Kohm’s time. Still, the fight continues for refuge advocates, who have new ways to apply grassroots organizing.

Dunaway had just finished writing Natural Visions, which analyzed how photos of nature affected environmental reform from the Progressive era to the first Earth Day in 1970. He wasn’t sure he wanted to spend his free time with more pretty pictures — until this one came along. The Banerjee photo, part of a Seattle photography exhibit, was captivating, a link to a place he needed to know more about. He wound up writing a journal article about Banerjee’s work, but the photo sparked something bigger: the start of Dunaway’s fascination with the 19 million acres of land that’s home to the largest wildlife refuge in the country.

Bright red long johns

When Dunaway launched his research for what he thought would be a wide-ranging history about the refuge and its perpetual threat of drilling, he came across an old Sierra magazine article about Lenny Kohm.

He tucked it into a file marked “not important.”

Then, in August 2014, he drafted an email to Kohm to request an interview. Perhaps he’d write a chapter on Kohm. Distracted by other projects, Dunaway set the note aside until October. When he was finally ready to hit send, he searched Kohm’s name online one last time.

The first result that came up was Kohm’s obituary. He had died in September.

That was an unpromising start in his quest to understand the slight, bearded man from Seattle who once posed for a photo wearing bright red long johns and a blue fishing hat.

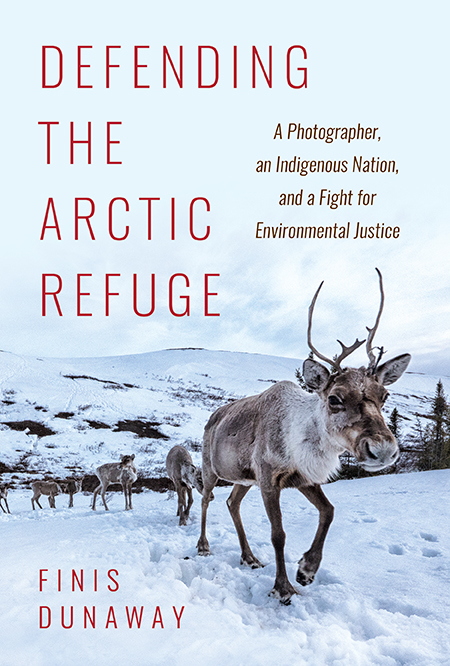

Telling Kohm’s story would take the interviewing skills and dogged persistence of a journalist: Despite Kohm’s reputation in refuge lore, big media outlets like The New York Times never profiled or even quoted him. Whenever Dunaway came upon an unexpected document referencing Kohm’s Last Great Wilderness slide show, “I could feel my heart rate quicken,” he wrote in his book published this year, Defending the Arctic Refuge: A Photographer, an Indigenous Nation, and a Fight for Environmental Justice.

Lenny Kohm, above, created a slide show of his photos of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and exhibited it in every state except Hawaii. The show cemented relationships among environmentalists and the people of the Gwich’in nation, who worked together to get congressional votes on the refuge to go their way time after time. (Courtesy of Lenny Kohm ’93)

Dunaway discovered a man who had struggled to find fulfillment until he found the Arctic. Born in Seattle in 1939, Kohm started playing drums at 14 and trained at the acclaimed Berklee College of Music in Boston. For 15 years, he made it as a journeyman drummer. Knowing he wasn’t the next Max Roach, he quit music and moved to the Art Farm, a former turkey farm in Sonoma, Calif., with studios for artists. He ran a pharmacy photo department and developed into a skilled photographer.

Yet, he hadn’t found meaning. Twice divorced and father to two daughters he seldom saw, Kohm was despondent until he traveled to Alaska for a photoshoot, hoping to sell the results to a magazine. He viewed the oil fields of Prudhoe Bay followed by the Arctic Refuge coastal plain — where more than 200,000 Porcupine caribou migrate from Canada each year to give birth. It brimmed with life, including a grizzly bear who towered on hind legs to get a good look at Kohm.

The next stop was the Arctic Village, a Gwich’in community 100 miles above the Arctic Circle, where a congressional field hearing on Arctic drilling was poised to start. Gwich’in leaders had traveled from Old Crow Yukon in Canada to testify how drilling would harm their livelihood and very existence. Kohm was upset at the legislators’ response: “A 30,000-year-old culture had 18 minutes to defend itself! That moment for me was an incredible epiphany.”

But Gwich’in leader Norma Kassi told Kohm that if he really cared, he would come to her village of Old Crow to see why the issue was so important to her people. Old Crow isn’t accessible by roads; people fly or canoe in. Kohm spent 10 days there, talking with residents, joining caribou hunts and learning about the connections among people, animals and land. He emerged transformed.

Kohm wasn’t an activist then, but he believed people could bring about political change. His belief was soon proven right in his own California congressional district. Kohm and friends screened a short film on the Arctic Refuge many times for local audiences there, who in turn “put over 8,000 letters on Congressman [Douglas] Bosco’s desk” to save the land, Kohm said. Though Bosco, an influential Democrat who leaned in favor of drilling, never became a full-throated advocate for the refuge, he stood with its supporters on a crucial vote for its protection.

Kohm and his friends wanted to try the same technique across the U.S. with their own documentary film. In the late 1980s, when funding for a movie didn’t come through, they created The Last Great Wilderness slide show and made three copies so that Kohm and others could tour with it.

The production featured refuge photos by Kohm and others, plus stirring music and narration to spark interest in a faraway place most people would never experience. Soon after, Kohm “took the show on the road,” Dunaway wrote.

“Teaming up with Gwich’in spokespeople from Alaska and Canada,” Dunaway wrote, “he gave as many as 200 presentations a year” in churches, libraries, schools, wherever he could,” reaching 49 states. Only Hawaii eluded him.

Kassi was one of roughly 50 Gwich’in who traveled with Kohm through the years. The tour stops sometimes attracted local media attention, and Kassi had to fight off nerves before making her first speeches to non-Indigenous people. Kohm soothed her. “Calm down, sister,” he said. “It’s all good. You live with the caribou, right? Just tell that story.”

Caribou meat in a portable smokehouse.

Kohm never dictated what his Gwich’in partners should say. They talked about their lives and experiences on the land, their respectful relationship with the caribou and how they used everything from the animal. Ken Kyikavichik, now grand chief of the Gwich’in Tribal Council in Canada’s Northwest Territories, described a rite of passage when his grandmother gave him a satchel made of caribou hide for his hunting supplies.

Kohm did have specific suggestions for his audiences. Write to your local newspaper or elected officials. Form a group to keep up the pressure on legislators. Tell others. And they did. Many people would stay engaged for years.

Kassi came to love Lenny Kohm as a brother. Her mother called him the “little white man who never sleeps” because of his dedication. Kohm was “a gift from the Creator,” Kassi said, “to help us, educate us, and build our confidence.”

Kindred spirits

Kohm was driven to protect the land that provides “life-sustaining habitat for caribou, polar bears, migratory birds, and other species,” Dunaway writes in Defending the Arctic. And after more than 50 interviews and a multiyear investigation, Dunaway believes the evidence suggests that Kohm’s work made a huge difference — not the slide show alone, but “all of these relationships that the slide show helped to bring into being” among the Gwich’in, environmentalists and beyond. Together, they got congressional decisions to go their way time and again.

Caribou Migration I, Coleen River valley, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, 2002, by Subhankar Banerjee.

Kohm and Dunaway are very different personalities: One was gregarious and over-the-top, a guy content to scrape together an income from one environmental group after another so he could advocate for the refuge. The other is quieter, thoughtful and sincere, a married dad of two teenagers. Still, in writing the book, Dunaway has inched a bit closer to Kohm, changing “from seeing myself as only a scholar, historian or academic to wanting to find ways that the work could in some small way contribute to a current campaign.”

That impulse took the form of a November 2017 op-ed written with Kassi for The Globe and Mail of Toronto against the Trump administration’s push for Arctic drilling. He wrote two more this year, for The Washington Post and The Hill, highlighting the issue as a matter of social justice. With the photographer Subhankar Banerjee — who has become a friend to Dunaway — he helped organize open-letter campaigns with scholars about the refuge, including a statement submitted to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management that attracted more than 500 signatories from 20 countries. Dunaway also testified to bureau leadership in Washington, D.C., and helped Banerjee organize a public hearing in Albuquerque.

Kohm believed in the power of “trickle-up” politics, ordinary people pushing elected leaders for reform. In the Arctic Refuge fight, it had worked for years. Could it still? “It’s maybe one of the only ways to affect change in a really meaningful, long-lasting way,” Dunaway said.

He acknowledged that partisan politics now pose more significant challenges than they did in Kohm’s time. Still, the fight continues for refuge advocates, who have new ways to apply grassroots organizing. The Bureau of Land Management held its first sale of oil and gas leases on the Arctic Refuge coastal plain on Jan. 6, 2021 — the day of the U.S. Capitol insurrection. Major oil companies said no thanks, their decision influenced by Gwich’in initiatives.

The Gwich’in and others had filed lawsuits against the Trump administration and “launched a banking and corporate campaign — part of a larger fossil fuel divestment movement — to pressure oil companies and financial institutions not to invest in Arctic drilling,” Dunaway wrote in The Washington Post. “Within a short period, the Gwich’in persuaded all the major banks in the United States and Canada to pledge not to finance Arctic drilling. These victories, together with falling oil prices and the pandemic-induced global recession, led to the lackluster sale on Jan. 6.”

Gwich’in leader Sarah James spoke at the Arctic Refuge rally in Washington, D.C., in 2005. (Photo by Subhankar Banerjee)

An Alaskan state-funded corporation did pursue drilling opportunities, but as of August, President Joe Biden had suspended the nine leases that were sold pending an environmental review. The corporation has vowed to move forward with predevelopment planning and permitting.

Not all parties who have a stake in the outcome agree. The Federalist quoted one of Dunaway’s op-eds in a column accusing the Gwich’in of hypocrisy; the publication said the tribe tried to lease its land in the Alaskan Venetie Reserve for drilling in the early 1980s, only to find it unproductive. Meanwhile, some Iñupiat leaders from a refuge community support oil and gas extraction and have lobbied in favor of it.

Dunaway said the issue is complex, but news stories often pit the Gwich’in and Iñupiat against each other. As he sees it, the Gwich’in are choosing a strategic alliance with environmental groups “for their own food sovereignty and cultural survival.”

Lenny Kohm “semi-retired” from Arctic work in 2001, moved to North Carolina and became an advocate against mountaintop-removal coal mining. Although Dunaway hasn’t dedicated decades to environmental advocacy as Kohm did, Kassi doesn’t downplay Dunaway’s contribution to the refuge’s survival. Dunaway is “another brother as far as I’m concerned.”

Each moment along his journey to learn about Kohm imprinted itself on Dunaway, like the careful unfurling of a mystery novel. The chase was part of the thrill. “Of course, I can’t say this for certain,” Dunaway said, “but I doubt that I would have become so fascinated and obsessed with [Kohm’s] story had I met him.”

Dunaway usually would be searching for his next writing project by now. But he is not so eager to move on this time. The Arctic Refuge and the community supporting it have worked their magic.

“Lenny and Finis are definitely kindred spirits, I’ll tell you that,” Kassi said. “Finis is carrying that spirit and the knowledge. It was all meant to be that he would be so touched by this little man that came to the Gwich’in people.”

Andrea Cooper is a freelance writer based in Charlotte.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.