The Art of Perseverance

Posted on July 1, 2019

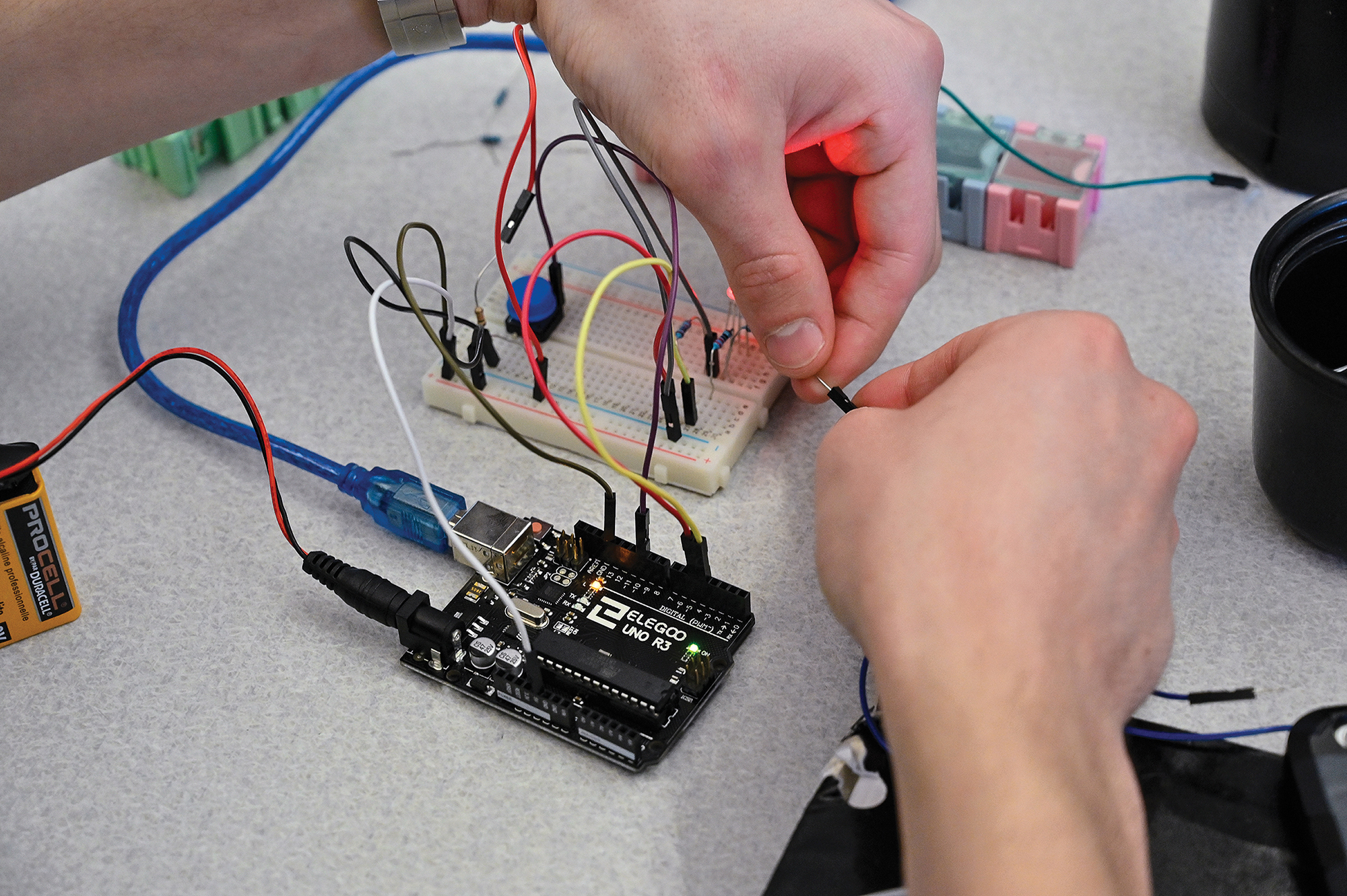

Glenn Walters teaches students in his applied science class to create an LED circuit. (Photo by Grant Halverson ’93)

Design. Build. Screw up. Repeat.

Glenn Walters ’05 (PhD) once had no interest in being in a college classroom — behind the lectern or in front of it.

“I was probably not very likely to be involved with a university whatsoever when I was in high school,” said Walters, research associate and director of the Environmental Science and Engineering Design Center in the Gillings School of Global Public Health. “I didn’t see the point. I was more interested in doing stuff, always tinkering, tearing things apart and playing with them.”

Filling gas tanks in 15-below weather for motorists headed to the Lake Placid Olympics changed his mind.

Forty years and a doctorate in environmental science and engineering later, he stands before a class of 25 Carolina students twice a week and tries to change their own entrenched thinking about a college education — namely, the belief that it can be validated like a parking stub, filled like a prescription. In “Introduction to Design and Making,” a course offered by the department of applied physical sciences, Walters challenges students to fail, in the best possible sense.

Pairs of students are given a kit containing a circuit board, wiring and color-emitting diodes that can be combined to create a range of colors and display options when connected to a computer. (Photo by Grant Halverson ’93)

APPL 110’s assignments, which range from creating a wooden toiletries organizer to building software-controlled circuits, are exercises in planning, designing and prototyping. Students tackle the design thought process in class, drawing sketches and conferring with their team members. They each spend an average of 44 additional hours outside of class, training to use BeAM equipment and building their projects in the makerspace.

But before they can do any of that, they have to let go of the limiting habits they’ve picked up in secondary schools, the ones that emphasized testing results, Walters said. He spends the first month of each semester training students how to discover answers rather than simply reciting them.

More BeAM coverage

The Student Body Shop

The BeAM School of Engineering

Can I Make You Something From the Davie Poplar?

A common conversation might go like this:

Student: “It seems like I’m going to have to redesign this thing a lot before it will work.”

Walters: “Yeah.”

“Is there any way around that?”

“No.”

“They want answers that are definitive in a way that aren’t consistent with how you approach design and making.”

Walters does give them a list of specifications for each build that will result in a B, plus some ideas for “stretch goals” to get a higher grade. Then, when they turn in a project that meets C- or B-level work — even late work — he tells them, “If you want another week to take this to an A, you can do that. But you better bring me an A.”

“I don’t have an engineer’s brain,” said Abbey Cmiel ’19, who majored in global studies and who took Walters’ class last spring. “But the way [Walters] teaches means the process of making is so much more approachable. It’s more about growth.”

Students are incredulous when Walters proffers this deal. “You’re going to give me more time and a higher grade? What’s the catch?” But that’s how making and inventing works in the real world, he said. Like pumping gas in a Vermont winter, the first decisions you make often are not your best.

“But if you take a little longer, it’s great, and the response to your design will be better,” he said. “Making enriches the content of any course, but it has the much more profound effect of expanding the way that people approach problems. When people ask me what I want students to get out of the course, my answer is perseverance. That’s it. That’s the lasting material that really matters.”

“I don’t have an engineer’s brain,” said Abbey Cmiel ’19, who majored in global studies and who took Walters’ class last spring. “But the way [Walters] teaches means the process of making is so much more approachable. It’s more about growth.”

— Beth McNichol ’95

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.