The Student Body Shop

Posted on July 1, 2019

The Murray Hall makerspace. (Photo by Alex Kormann ’19)

There’s a long-standing discomfort with the notion that college students know Thoreau but not “measure twice, cut once.” Carolina is at work on that as a leader in the maker movement.

by Beth McNichol ’95

At first glance, you might mistake the space you are looking at on the first floor of Murray Hall for a student lounge with an industrial-chic decor. The exposed pipes running the length of the ceiling are enough to make you suspicious.

But then your eyes slide to a dozen tables with butcher-block tops and metal legs sitting on a polished concrete floor and the ventilation tubes for soldering that dangle above them. You see glass partitions that separate a metalworks area from a woodshop, with its drill press and band saw and router — serious machinery for serious builders. You spot Kate Goldenring, a computer science major, reupholstering a tired sofa with recycled shopping bags that have been sewn together in a crosshatch pattern.

Kate Goldenring ’19 works on upholstery made from recycled shopping bags. Her “makes” include a chessboard for her father, a wooden map of the U.S. for her boyfriend, earrings for her mother. (UNC photo by Jon Gardiner ’98)

Goldenring ’19 — who graduated into a desk job at Microsoft — casually ticks off a list of other items she’s made with the machines in Murray: a chessboard for her father, a wooden map of the United States for her boyfriend, earrings for her mother. Then, above the thunk and whir of hand tools, 3D printers and sewing machines inside the 3,200-square-foot space, Goldenring utters words you might not have expected you’d hear from a student in Chapel Hill.

“The laser cutter,” she says, “is like my best friend.”

What in the name of Bob Vila is going on here? How is it this liberal arts haven is humming to the whine of a miter saw?

More BeAM coverage

The BeAM School of Engineering

The Art of Perseverance

Can I Make You Something From the Davie Poplar?

What you see, smell and hear here is shop class and home economics refurbished for the digital age. Hundreds of willing participants know this as BeAM, or “be a maker,” UNC’s answer to the worldwide makerspace movement — the collaborative culture of making physical objects using both digital and traditional tools. Now entering its fourth year, BeAM makerspaces are leading the Carolina community and its students through a re-emergence of know-how, in and out of the classroom.

In their first two years alone, the makerspaces — in Murray (the 9-year-old chemistry companion to Venable Hall), Hanes Art Center and Carmichael Residence Hall — attracted 4,000 unique users, including 160 classes that incorporated making into their curriculum, totaling more than 33,000 hours of use and an average of 142 visits daily.

Free of charge and open to students, faculty and staff, BeAM is governed by the philosophy that personal making is just as important as academic making; the makerspaces provide the training, tools and materials for visitors to create to their heart’s content. On any given day, you might find a freshman creating a Greek mask for a drama assignment and a graduate student designing a lab tool sitting side-by-side in front of the 3D printers, giving each other guidance.

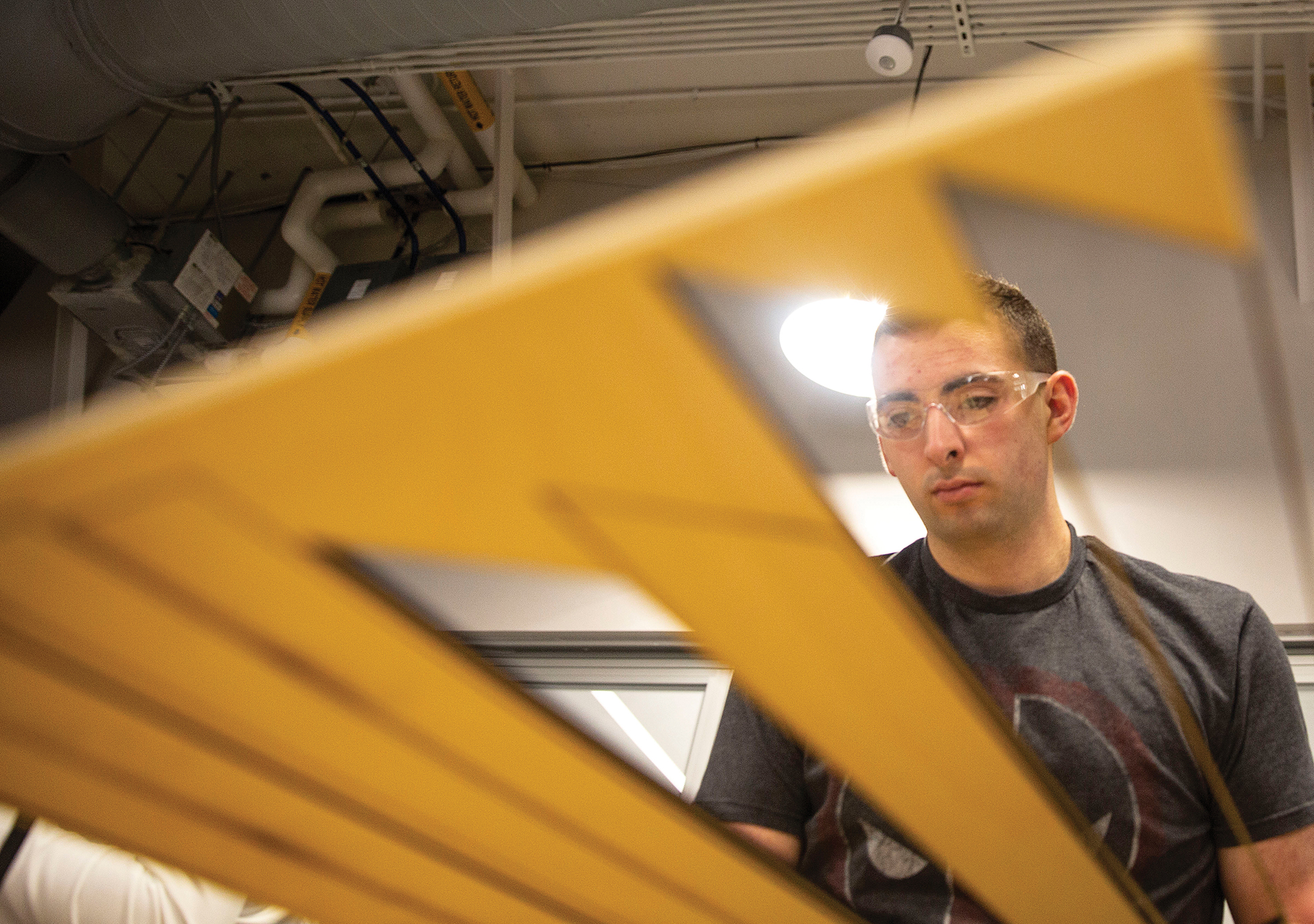

Rising junior Chris Cataldo in Hanes Art Center, an unapologetically rugged, windowless woodshop whose technical adviser says has a “special aura.” (Photo by Alex Kormann ’19)

You might see fraternities printing their own T-shirt designs or using the vinyl cutter for the perfect-sized laptop sticker. Or, last semester, economics major Jacob Moore ’19 creating a planter in the shape of Baby Groot from Guardians of the Galaxy II … just because.

Chris Scerbo, a BeAM staff member and pre-med student, said he could print a 3D molecule for personal study, teach someone to use the laser cutter or design and build his own barstool in the woodshop.

“It’s nice to know you have these skills to rely on,” said Scerbo, a rising junior from Greensboro who’s seen researchers churn out 3D-printed pipettes and missing screws for their labs.

“Whenever I have to ask, ‘How am I going to solve this issue I have?’ I already know the answer. Just get it done.”

Owning helplessness

That prevailing attitude — just get it done — is a sea change from where many students were in 2013, when the concept for BeAM first was floated. A group of instructors across campus, from disciplines as varied as art and physics, discovered they shared the same daily frustration: Their students were chock-full of theoretical and digital smarts but woefully lacking in practical knowledge. They began meeting to commiserate and talk about solutions.

Richard Superfine, the Taylor-Williams Distinguished Professor of physics and astronomy at UNC, reported that his graduate students “barely even knew how screws work.” Lab assistants routinely visited Glenn Walters ’05 (PhD), director of the Environmental Sciences and Engineering Design Center, asking him for help with fittings for gases and liquids after “slamming things together, wrapping them with a whole lot of tape and hoping for the best — or just throwing their hands up and saying, ‘We can’t do it.’

“They don’t always realize it,” said Walters, a research associate in the Gillings School of Global Public Health who is known as UNC’s maker extraordinaire, “but students just own their helplessness.”

A 3D printer in the Carmichael BeAM lab creates a plastic replica of the Iron Throne from Game of Thrones.

These were flabbergasting facts for people like Walters and Superfine, who not only had built a career and a life out of working with their hands but who had grown up in a generation that hadn’t yet buzz-sawed its high school industrial arts classes — the makerspaces of yesteryear — in favor of wall-to-wall Advanced Placement courses, giving in to the demands of the competitive college admissions race. Pushing industrial arts to the background, a move that has been happening in school systems nationwide for more than two decades, was like removing a structural beam from a home; like building a square wheel and saying, “Good enough.”

“We define being human largely in terms of using and making tools,” said Superfine, who holds patents for instruments he’s built for his research and furnishes his home with furniture he’s made. “That’s how we define what it means to be intelligent.”

“Every day, you hear someone say, ‘Well, I tried this, and it didn’t work. So, I had to try something else, and now finally everything’s coming together.’ They find their confidence.”

— Anna Engelke ’10, BeAM staff member

“Throughout their academic career, students don’t have an experience of being empowered to do things for themselves,” added Walters, “and what the things are aren’t as important, as long as it’s something.”

After polishing their bona fides to a blinding gleam to gain admission, students also frequently arrive on campus having allowed their muscles to atrophy, said D.J. Fedor, a machinist and instrument maker who has worked in the manufacturing industry and for NASCAR.

But making requires a high tolerance for trial and error. That’s why, when Walters, Superfine and a handful of representatives from other disciplines across campus pushed for the opening of the first BeAM in the basement of Hanes Art Center in late 2015, Fedor was skeptical it would work.

“They come to campus afraid to fail,” said Fedor, who now is the technical supervisor for BeAM at Hanes, an unapologetically rugged, windowless woodshop that Fedor says has a “special aura.” “If you tell a Carolina student to take nine steps, they’ll take nine steps. They won’t cut you short and take six or seven. But only a select few push it, try to get to 10. It’s: ‘This is what you told me to do, so this is what I’m going to do.’ ”

Free of charge and open to students, faculty and staff, BeAM is governed by the philosophy that personal making is just as important as academic making. (UNC photo by Jon Gardiner ’98)

That tendency made BeAM feel even more necessary, especially as its results began to show. Lost in their creativity, let loose in the playground of the makerspace, students eventually stop thinking about success and failure, said Anna Engelke ’10 (’17 MA), program coordinator for BeAM.

They begin to see all their projects as an exercise in persistence.

“Every day, you hear someone say, ‘Well, I tried this, and it didn’t work. So, I had to try something else, and now finally everything’s coming together,’ ” Engelke said. “They find their confidence.”

The life-changing magic of making

The goal is that that confidence begins to transfer to other areas of students’ lives, rounding out the square and squeaky wheels on which they sometimes hobble onto campus — which is why BeAM administrators don’t prioritize a laryngoscope for the lab over a key chain for a best friend.

(That’s good news for students, who crowd into BeAM locations the week before winter finals each year to work on handmade holiday gifts. “Picture what a New York deli is like right before Thanksgiving,” said Fedor of the maker rage. “Last year was so intense, fisticuffs nearly broke out. It was close, it really was.”)

BeAM use is always first come, first served.

“When they’re using the laser cutter to make a Mother’s Day card, they’re learning even more about how to use the tools in the space than if they were only using BeAM to fulfill a class assignment,” said Superfine. “So when they come to an invention they want to pursue, they’ll have even more skills to draw from.”

Such accessibility is unusual among college makerspaces nationally, which frequently charge fees, require project approval or leave the actual making to librarians who take and fulfill orders for the 3D printer, said Walters. (Carolina has similar fulfilment in the Kenan Science Library.) Many makerspaces are housed in engineering schools and “restricted to engineering students — or even worse, engineering students doing class projects,” Superfine said.

Tooling around: choices in Murray Hall and woodworking equipment in the Hanes Art Center. (UNC photo by Johnny Andrews ’97)

Ironically, campuswide makerspaces rarely gain traction at universities with engineering or design schools, where machinery is coveted by those majors and held territorially captive.

Broad buy-in never has a chance to happen. Those complaints explain why some N.C. State and Duke students come to play at BeAM. A One Card will get you in, which non-Carolina students may have for collaborative work in labs or elsewhere on campus.

“Duke students come here to do stuff because we have better facilities than they do,” Walters said. “We are really at an advantage here in that we don’t have an engineering school.”

It also means that arts and humanities courses at UNC are using BeAM as much as STEM fields, said Engelke, who helps professors integrate making into their coursework. For every biomedical engineering student making prosthetic prototypes, there’s a studio art minor like Lauren Ralph ’19, who designed and built a panoramic pinhole camera for her “Movie Making Machines” course — hand-sketching and optimizing it on Adobe Illustrator, then creating its many parts using a laser cutter. Fascinated by the small tweaks that could change the device’s use, Ralph kept returning to BeAM to refine the camera long after she’d turned it in for her course, Engelke said.

“I see that with a lot of students,” Engelke said. “They might do a project in their courses, and the momentum of the experience carries with them later. ‘How could I continue this or expand on it?’ ”

Because they come to campus digitally savvy, students who train to use BeAM tools apply them to situations even instructors find surprising. Classics major Andrianna Dallis ’19 frequently creates her own replicas of ancient artifacts for tactile study at home. She might snap a picture of a museum object, for example, then upload it to a software program that measures its dimensions for 3D printing.

“Just the fact that it’s second nature to her to think of doing that is mind-blowing,” Walters said. “They very quickly put it all together.”

Abby Gancz ’19

That transfer of knowledge has been transformative in the archaeology department. When Abby Gancz ’19, who majored in biostatistics, began working in the archaeology lab, she had the idea to reproduce artifacts for faculty using 3D printers.

“She led all the faculty on that one,” said Walters, who added that the department is now hammering out a plan to have students build field equipment to replace older tools. “For a couple of years, she was the go-to person. It was, ‘Just give it to Abby; she’ll take care of it.’ That got her an internship at the Smithsonian.”

Gancz called BeAM “absolutely fundamental” to her college experience, giving her technical knowledge and research skills she said she’ll use next year as a graduate student in biological anthropology.

“So, is BeAM life-changing?” Walters asks. “Yeah. In a lot of ways, it is. Abby had never made anything in her life before she came here. It wasn’t on her radar, but it’s completely shaping the direction that she’s going as she leaves here.”

Too big to fail

To use BeAM, students, staff and faculty first complete an hourlong general orientation in which they make what Fedor calls a “two-piece chicken dinner” — a simple object that serves to decrease the intimidation factor.

“You cut a piece of wood, you drill a hole, you hot-glue some stuff in there and you build this silly little thing,” Fedor said. “We force you to put a handsaw in your hand, a screwdriver, a cordless drill — and it makes you want to come back and do more.”

After that, makers complete training workshops, led by BeAM’s student staff members, for any specific skills they want to learn before they are set free on those machines — such as woodshop, laser cutting and 3D printing.

Fedor and other BeAM administrators said the idea of opening BeAM training and use to alumni also has been floated, but graduates within driving distance shouldn’t dream of making their own Baby Groot planters just yet. One big reason: cost.

“We don’t have the budget for the materials we already provide,” Walters said of the sheets of vinyl, wood, acrylic and 3D printer filament available free for use.

It raises the question: How does BeAM keep going? Walters is blunt: “We’re too big to fail. It would be embarrassing for the University for us not to keep going. We’ve never been comfortable with that as a funding model, but it works for now — and we’re constantly working on sources of revenue.”

Many of those funding questions will have to be answered soon; the University is hiring a director for the BeAM network to marshal its future, including a fourth location envisioned for the new Institute for Convergent Sciences that’s planned to have 15,000 square feet of machinery, drones and robotics.

What started as a solution has quickly become an institution at Carolina, and it isn’t going anywhere soon. BeAM has become an emblem of the very empowerment it was born to spread.

Or as Kristy Reed ’19 said, “It’s satisfying to make your own stuff — especially when you can make something that works exactly how you want it to.”

Beth McNichol ’95, a freelance writer based in Raleigh, is a former associate editor for the Review.

Thanks for reading the Carolina Alumni Review

Carolina Alumni members, sign in to continue reading.

Not yet a member? Become one today.